Bagacum (Bavay)

Q2048162Bagacum: capital of the Nervii, a tribe in northern France/western Belgium. The city is now called Bavay.

Early History: The Nervians

In the Roman period, Bagacum (modern Bavay in northern France) was inhabited by the Nervians, a Belgian tribe. These people are unmentioned in our sources prior to Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul; the first and most important source of information about the Nervians is Caesar’s own account in the Gallic War. In those days, they inhabited the region between the rivers Scheldt, Sambre, and Meuse. Caesar mentions them as dangerous opponents, who came close to defeating the Roman legions in 57 BCE in the battle of the Sabis River (57 BCE) and in 54 BCE during the siege of the camp of Quintus Tullius Cicero (brother of the famous orator).

The Nervians did not live in what we would call cities, but in oppida or fortified settlements surrounded by walls of earth and wood (the murus Gallicus). Probably, Bagacum was not one of these oppida. although the name is Celtic and, therefore, antedates the Roman occupation. However, although Bavay has offered several Late Iron finds, they are not enough to assume that there was a Belgian settlement.

The solution may be that Bavay is a continuation of an earlier settlement: about twenty kilometers to the south lies Avesnelles-Flaumont, which may have been an earlier capital of the Nervians. It is certainly possible that the Romans, after exterminating the Nervians (who suffered heavily in the battle at the Sabis), repopulated the area. That would not be unique: Tongeren, Cologne, and Nijmegen are other examples of towns with no continuity from the Iron Age to the Early Roman Period.

All Roads Lead to Bagacum

The position of Bagacum as a node in the network of Roman roads suggests that it was, on its present location, founded by the emperor Augustus's right-hand man Agrippa, who created this network in 39/38 or 20-18 BCE. It was part of the establishment of the province of Gallia Belgica, with Durocortorum (modern Reims) as capital and Bagacum as northwestern center. The Nervian territory was enclosed by that of the Menapians in the north, by the Atrebates in the west, by the Ambiani and Viromandui in the south and by the Tungri in the east.

From Bagacum, there were straight roads to

- the east-northeast to Tongeren and Cologne (the so-called "Chaussée Brunehaut"),

- to the east to Dinant,

- to the east-southeast to Augusta (Trier),

- to the southeast to Durocortorum,

- to Cambrai and Vermand in the southwest,

- to Arras in the west,

- to Blicquy in the northnorthwest,

- and to Tournai in the north.

Many modern roads still follow the tracks of those old roads. They are often named "Chaussée Brunehaut", after the Frankish queen Brunhilda who - according to a fourteenth-century legend - repaired the roads.

Early Roman City

Initially, Roman Bagacum was a modest town. On the site of the present museum there were houses built from perishable material, wells, and storage places for manure. Some workshops were to be found in the neighborhood. However, a now lost inscription that was destroyed during the Second World Warnote proves that Bagacum was not an ordinary place. Between 4 and 7 CE, it was worthy of a visit of the intended successor of the emperor Augustus, Tiberius.

Ti(berio) Caesari Augusti f(ilio)

divi nepoti adventu(i)

eius sacrum

Cn(aeus) Licinius C(ai) f(ilius) Vol(tinia) NavosTo Tiberius Caesar, son of Caesar Augustus, grandson of the divine Caesar, on the occasion of his visit, has Gnaeus Licinius Navos, son of Caius, of the Voltinian district, dedicated this.

As administrative center of a civitas, Bagacum had its own magistrates. Some magistrates are known: Tiberius Julius Tiberinus, was duumvir (a kind of mayor), and we read about a Lucius Osidius, who acted as priest of Roma and Augustus in Lyon, while we also know a Marcus Pompeius Victor, quaestor of the Roman citizens.

Bavay, the basilica on the forum |

Bavay, Forum |

Bavay, Forum |

Bavay, shops along the forum |

Roman City

Bagacum expanded quite rapidly. Its function as political center necessitated the construction of a monumental city center, the famous forum, surrounded by cryptoporticoes. The basilica, for example, was one of the largest in the Roman world, larger than its counterpart in Carthage.

It would seem that the inhabitants were loyal to the government: Tacitus mentions Nervian soldiers as supporting the pro-Roman leader Claudius Labeo during the Batavian Revolt (69/70 CE).note

The city continued to flourish. In the second century, the city had expanded to some 45 hectares. Although the town was quite modest compared to Amiens (150 hectares) or Trier (more than 200 hectares), Bagacum attracted enemies. In 172 CE, the Chauki launched a devastating campaign against western Belgica, where the capital cities of the Morini and the Nervians, Tervanna and Bagacum, were so extensively damaged that they had to be rebuilt completely.

Bavay, Tomb of a baby |

Bagacum, Bronze statuette of female deity |

Bavay, Lampstand |

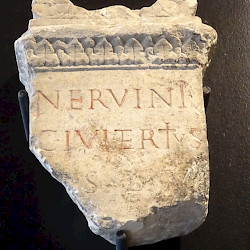

Bavay, Roman inscription |

Late Antiquity

In the late second century, the Roman Empire still had the means to rebuild cities. Bagacum was less lucky after the defeat of the Gallic Empire. The new ruler, Aurelian (r.270-275), massacred many troops and transferred the remainder, allowing the Franks to sack the northern cities. Cologne was plundered, Maastricht put to the torch, Tongeren gutted, Bagacum leveled to the ground. It never recovered.

The emperors Diocletian (r.284-305) and Maximian (r.285-305) restored order, but Bagacum was replaced by Camaracum (modern Cambrai) as main town of the Nervians. Whether Bagacum was affected by the invasions of northern Gaul at the end of the fourth century or the raids in the fifth century is not entirely clear. The frontier between Germanic and Romance languages has always been north of Bavay, suggesting that (unlike French and Belgian Flanders the area was not heavily settled by Germanic invaders.

In any case, the ancient forum area, measuring some four hectares, became a fort, surrounded by an impressive wall. Archaeologists found traces of fire on several places, which could indicate that the city was burnt. However, the town appears not to have been abandoned because private houses were discovered on the site of the forum. The cryptoporticoes remained in use at least until the fifth century.

Research

Archaeological research in Bavay got off to a good start thanks to the efforts of Maurice Hénault, archivist of the Valenciennes Library. This man was active on the site for about thirty years. From 1923 until 1934, he published a journal Pro Nervia in which he published the results of his investigations. In 1936, he was succeeded by Henri Biévelet, who started the major excavations on the site in 1942 and continued until 1976. He uncovered most of the cryptoporticoes and the esplanade in front of the basilica. After 1976, the work was continued by Jean-Claude Carmelez, curator of the Bavay Archaeological Museum. In 1988/1989, the site was then recognized as one of the thirty French national sites entitled to further research, which is done now by the Centre for Archaeological Studies of the University of Lille.

The best preserved remains are the impressive porticoes, the south-facing terrace with the remains of several shops, the cryptoporticoes, the central square of the forum, the remains of the basilica, the habitat area to the south of the forum and the rampart from the Late Imperial period.