Babylon

Q5684Babylon was the capital of Babylonia, the alluvial plain between the Euphrates and Tigris. After the fall of the Assyrian empire (612 BCE), Babylon became the capital of the ancient Near East, and king Nebuchadnezzar adorned the city with several famous buildings. Even when the Babylonian Empire had been conquered by the Persian king Cyrus the Great (539), Babylon remained a splendid city. Alexander the Great and the Seleucid kings respected the city, but after the mid-second century, the city's decline started.

Beginnings

The Greek word Babylon is a rendering of Babillu, a very old word in an unknown language. When Mesopotamia was infiltrated by people who spoke a Semitic language (Akkadians or Amorites), they recognized their own words Bâb ("gate") and ili ("gods") and concluded that this place was "the gate of the gods". (A similar etymology was invented for Arbela.)

The oldest building phase of Babylon cannot be recovered. The city was (and the ruins are) situated on the banks of the river Euphrates, and the remains of the oldest city are below groundwater level. From written sources, however, we know that the city became important after the fall of the empire of the Third dynasty of Ur, when the Amorites had invaded the area.

Old Babylonian Empire

Mesopotamia, and even though the political power of Babylonia had its ups and downs in the next millennium or so, Babylon remained the cultural capital of the ancient Near East.

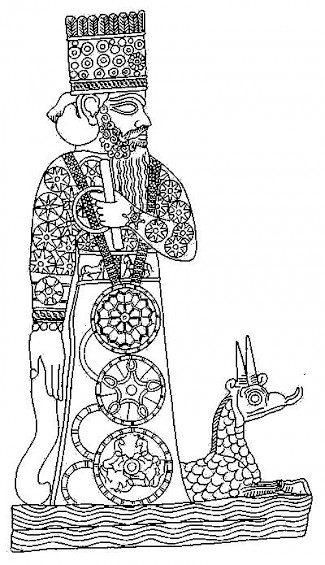

One of the results was that the hitherto unimportant city god of Babylon, Marduk, gained prestige. He superseded the Sumerian supreme god Enlil, took over many of his attributes, and now became the head of the pantheon. The syncretism is expressed in the words that Marduk is "the enlil of the gods", an expression that is perhaps best translated as "president of the council of gods".

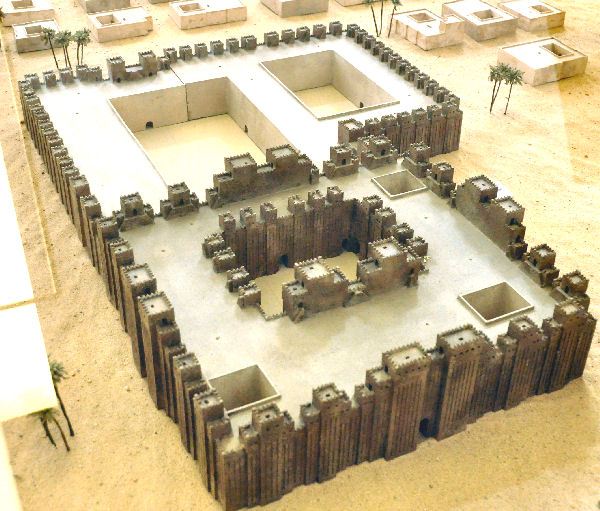

The famous temple of Marduk, Esagila, and its ziggurat, Etemenanki, were considered to be the foundation of heaven on earth. In the creation epic Enûma êliš, Babylon is the center of the universe, an idea that is also implied (or parodied?) in the Biblical account of the "tower of Babel", in which the confusion of languages is followed by people spreading all over the world out of Babylon.

The theological fact that Babylon was the center of the world, was reflected in several aspects. One of these was the New Year's Festival (Akitu), during which gods left their cities, visited Marduk, and announced their plans for the new year. Several quarters of Babylon received the name of important Babylonian cities (e.g., Eridu), as if Babylon were some sort of microcosm.

Cultural Capital

As cultural capital of the ancient Near East, even a politically powerless Babylon was an important city, which created a problem to the Assyrian kings, who conquered Babylonia in the eighth century. From Tiglath-pileser III (r.744-727) on, they had themselves enthroned as kings of both Assyria and Babylon: by uniting the city in a personal union with their empire, they wanted to express their respect for the Babylonian civilization, institutions, and science. However, the Babylonians revolted under Marduk-apla-iddin (703; the Biblical Merodach Baladan), and king Sennacherib sacked the city in 689 - an act of terrible impiety, because he broke the "axis" between heaven and earth. Babylon's population was deported to Nineveh and the site was left alone for some time.

Finally, king Esarhaddon (r.680-669) allowed the people to return. A text says that the gods had decreed the Babylon was to be in ruins for seventy years, but that they regretted their harshness, turned the tablet of destiny upside down, and allowed the people to return after eleven year (in cuneiform, the numbers 70 and 11 relate to each other as our 6 and 9).

A new model of ruling the city and its environs was found by Aššurbanipal (r.668-631), who appointed his brother Šamaš-šuma-ukin as king, but he revolted too (ABC 15), and again, Babylon was captured. Another brother served as king of Babylon, and in 627, the Assyrian king sent two of his relatives as governors. They were expelled by a Babylonian soldier named Nabopolassar, who had once fought in the Assyrian army but now started a kingdom for himself.

New Babylonian Empire

According to the Babylonian chronicle known as ABC 2, he was recognized as king on 23 November 626. This seems to have been the beginning of a series of insurrections against the Assyrians. In 612, Nineveh the Babylonians and Medes sacked Nineveh (text), and Babylon became the new political capital of the Near East.

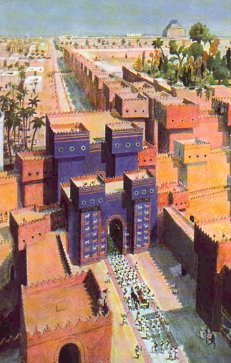

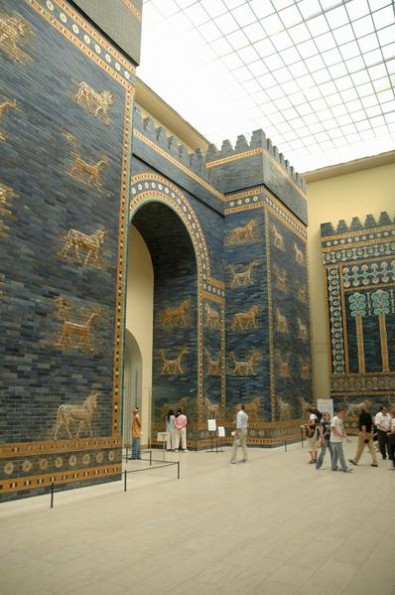

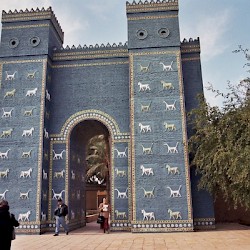

The son of Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar, ruled from 605 to 562 (more...) and is credited with rebuilding his capital as the most splendid city in the Near East. The famous blue walls and Ištar Gate are an example. Elsewhere, the royal palace was improved, the Etemenanki reconstructed, and somewhere in the city, a beautiful park seems to have been created, that has become famous as the "Hanging Gardens". Archaeologists have been unable to identify this monument, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, but perhaps this will change. For the time being, scholars believe that this park was either in Nineveh, or is nothing but a fairy tale.

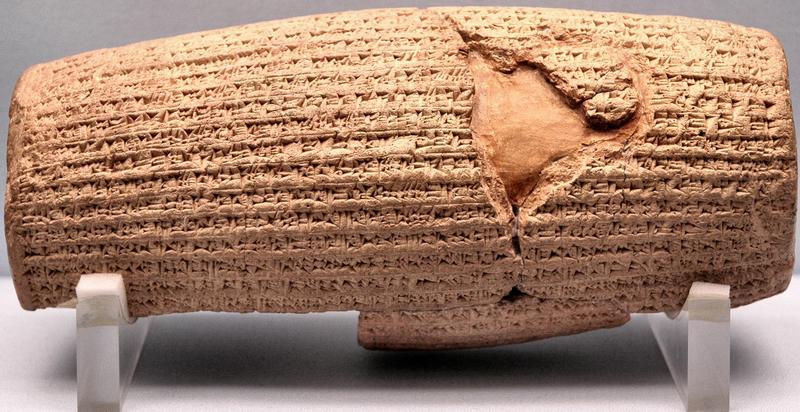

In 539, the brief period of the Babylonian political supremacy came to an end. The Persian king Cyrus the Great (r.559-530) captured Babylon (texts) and appointed his son Cambyses as king of Babylon. Like the Assyrian king, Cyrus admired Babylon as a cultural capital, and sought a way to rule the city while respecting its importance. In the Achaemenid royal inscription known as Cyrus Cylinder, the Persian conqueror presents himself as the chosen of Marduk - in other words, as a Babylonian.

Late Period

Later Achaemenid kings treated Babylon with just as much respect, although there were insurrections during the reigns of Darius I the Great (by the Babylonian leaders Nidintu-Bêl and Arakha) and Xerxes (in 484, by Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba). Reports by Greek authors (Herodotus of Halicarnassus and Arrian of Nicomedia) that Xerxes punished Babylon and removed statues are often misinterpreted. Whatever statue Herodotus says was taken away, it was not that of Marduk; the cult in the Esagila continued; and Babylonia remained an important center in the Persian empire. On the other hand, several Babylonian archives end in 484, and it is possible that when Xerxes captured Babylon, the city was looted.

Babylon, Palace wall |

Babylon, Neo-Hittite lion |

Babylon, Procession Street, Decoration, Lions |

Babylon, Gate of Ištar, Reconstruction |

In 331, the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great, who was fighting a war against the Persians, captured Babylon (text). Later, he intended to make the city his residence, and he ordered several building projects, like a large river port, a theater, and a reconstruction of the Etemenanki. Building activity related to the Esagila is mentioned in several cuneiform sources and continued as late as the early 280s, when the Seleucid crown prince Antiochus used his elephants to remove the debris (text).

Meanwhile, however, the founder of the Seleucid dynasty, Seleucus I Nicator, had ordered the building of a new city, Seleucia. This was meant as a Greek city, and crown prince Antiochus resettled Europeans that had been left in Babylon in Seleucia (text). For more than a century, Babylon remained a primarily Babylonian city. It was only Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r.175-164) who again started a Greek colonizing policy in Babylon (text). By then, the Greeks had started to tell fantastic stories about Babylon, where - for example - a large obelisk could be seen.

In this period, which is well-known from the Astronomical Diaries, we can discern at least five different population groups in the city, who had their own administrative institutions:

- The original Babylonian citizens, who were represented by the official named šatammu , i.e., the president of the council (kiništu) of the Esagila, the temple of Marduk.

- The Greek citizens (politai), under the authority of a "governor of Babylon" or epistatês. They met in the theater.

- The royal slaves, led by "the prefect of the king".

- "The people of the land", who are mentioned in our sources, and are probably the indigenous population on the countryside.

- The temple slaves.

A generation after the attempt by Antiochus IV Epiphanes to populate Babylon with Europeans, the Parthians conquered Babylonia (141).

The city suffered, but remained an important center of learning. For example, the Babylonian astronomers known as Chaldaeans were still studying the skies, and the Akitu festival was still celebrated. The Greek community still celebrated its festivals, followed the Hellenistic religious fashion by introducing the ruler cult, and organized athletic contests (more...).

Yet, it appears that the city's decline had begun. When the Roman emperor Trajan invaded Babylonia in 116-117, he was disappointed by the ruins. Still, as late as the late second century, texts were written in the Babylonian language, and the theater was restored (more...).

Modern Age

Babylon was excavated between 1899 and 1917 by Robert Koldewey, a pupil of the great Heinrich Schliemann. Unfortunately, Koldewey still had to identify many structures by using ancient Greek sources like the Histories of Herodotus of Halicarnassus and the Persian History of Ctesias of Cnidus. After all, cuneiform studies were, by then, still in their infancy. We now know that these authors were not very reliable, but still, Koldewey's Das wieder ertstehende Babylon is a fascinating must-read.

After this, a certain neglect of the archaeological remains of Babylon started. The British Museum owns a collection of almost 120,000 cuneiform tablets which are published very slowly, something that is among the greatest academic scandals of the modern age.

In the 1980s, the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein ordered repair works at Babylon, which, however, were not executed by archaeologists and restoration professionals. The result was disastrous, but even worse was to come: after the fall of the dictator in 2003, Polish soldiers used the archaeological site as military base.