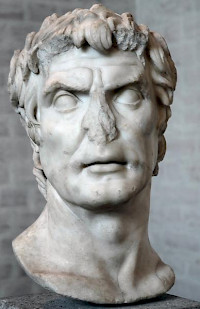

Mithridates VI Eupator

Q185126Mithridates VI Eupator (132-63): king of Pontus (r.120-63), enemy of Rome in first century BCE.

Early reign

Mithridates VI was surnamed Eupator and Dionysus to distinguish him from his father, Mithridates V Euergetes, who had been king of Pontus (northern Turkey) between 152/151 and 120. Euergetes was allied to Rome, which he supported during the Third Punic War (149-146). With this alliance, Euergetes could expand the power of Pontus from the shores of the Black Sea to central Anatolia, where he fought against king Ariarathes VI Epiphanes of Cappadocia and forced the Paphlagonian ruler Pylaemenes to bequeath his realm to Pontus. His capital Sinope was home to a hellenistic court, and Euergetes was willing to present himself in the Greek world as champion of hellenism in Anatolia. In 120, he was murdered in Sinope, and left his kingdom to his wife, the Seleucid princess Laodice, and their two sons, Mithridates Eupator and Mithridates Chrestus.

Civil war was inevitable, but the boys were still young and their mother was able to postpone the conflict. Yet, in 116 (?), Mithridates Eupator was able to remove his mother from the throne, and not much later, his younger brother disappeared from the scene. Maybe the ruler of the Seleucid empire, Antiochus VIII Grypus, wanted to intervene on behalf of Laodice, but the Seleucids were involved in a civil war. In this way, Mithridates Eupator became sole ruler of Pontus.

The young king continued his father's expansionist policy. In 115/114, he crossed the Black Sea and intervened in a conflict between the hellenistic kingdom at the Crimea (the "Bosporan kingdom") and its northern neighbor, the Scythians. The result of this intervention was that the Crimea was added to Pontus and a large part of the northern shore of the Black Sea became Mithridates' protectorate.

New successes were to come. Paphlagonia was finally inherited and shared with the king of Bithynia, Nicomedes III Euergetes. In 104/103, Colchis (modern Georgia) was added and not much later, parts of western Armenia were conquered as well. Until now, the Roman Senate had not been really interested: after all, Anatolia was far away and besides, Rome was involved in wars against the Numidian king Jugurtha and against the Germanic tribes of the Cimbri and Teutones. However, the conquest of Paphlagonia was not acceptable to the Senate, and the two kings had to evacuate the country they had seized.

Mithridates was not deterred. Almost immediately, in 101, he intervened in Cappadocia and Galatia (in central Anatolia), but again, the Romans were not happy with this state of affairs, and their praetor Lucius Cornelius Sulla put a new king on the Cappadocian throne, Ariobarzanes I Philoromaeus. Both men were to play a role in the next quarter of a century: Sulla became Mithridates' nemesis, and Ariobarzanes was to lose and regain his throne at least six times.

The conflict with Rome that was to last for the rest of Mithridates' life became inevitable in 94, when Nicomedes III of Bithynia died and was succeeded by Nicomedes IV Philopator. The king of Pontus wanted to install Philopator's brother Socrates Chrestus in Bithynia, which was unacceptable to Rome: the Romans feared that Mithridates, whose empire consisted now of all countries surrounding the Black Sea, would become too powerful if a puppet would be king in Bithynia. The immediate cause, however, was Mithridates' attempt to replace Ariobarzanes of Cappadocia with his son Ariarathes Eusebes.

In 90, the Senate sent Manius Aquilius to the east, and he restored Nicomedes to Bithynia and Ariobarzanes to Cappadocia. The Roman leader also urged Nicomedes to raid Pontus, thinking that Mithridates would understand the lesson. However, the king of Pontus, learning that the Romans were now also involved in a civil war against their Italian allies, decided to retaliate, and in 89, war broke out.

The First Mithridatic War (89-85)

Rome was unprepared. It had insufficient manpower to overcome its rebellious allies, and in 90, one of the consuls, Lucius Julius Caesar, had proposed to do concessions to the rebels. There were not enough Roman troops in Asia to protect this province; the fact that Aquilius had left the retaliatory raid against Pontus to Nicomedes IV of Bithynia suggests as much.

As a consequence, Mithridates started the war spectacularly successful. Within weeks, he conquered all of Rome's Asian possessions, hardly encountering resistance. In the spring of 88, he ordered the execution of all Romans and Italians in the conquered area. According to our sources, about 80,000 were killed. Any possibility to reach a compromise was now blocked.

In the summer, Mithridates was invited by the Athenians to liberate them from the Romans, and he sent his armies across the Aegean. In Athens, a man named Aristion became tyrant, and elsewhere Mithridates' general Archelaus was successful. Things would have gone terribly wrong for Rome, had not Quintus Braetius Sura, the deputy (pro quaestore) of the governor of Macedonia, offered resistance. Only parts of Greece were lost; Macedonia remained under Roman control, although another Pontic army was active in the north and captured Amphipolis.

At the same time, the Romans and their allies had finally ended their conflict, and the Romans sent their consul Sulla to the east. However, his appointment had been contested by his rival Gaius Marius, and Sulla had not been able to leave until he had marched on Rome and won a brief civil war. It was 87 when he finally crossed the Adriatic Sea, landed in Epirus, marched with five legions on Athens and started to besiege Aristion. At the same time, he tried to take Piraeus, the Athenian port, which was defended by Archelaus.

The war was, even for ancient standards, harsh and bitter. The Mithridatic forces had already looted the sanctuary of Delos to obtain money to hire mercenaries; with the same purpose, the Romans looted Delphi. This was unusual. After a long siege, Athens and Piraeus fell. The columns of the temple of Zeus Olympius were sent to Rome, where they were used to decorate the temple of the Capitoline Jupiter.

Mithridates' general Archelaus managed to escape and joined the army that had been operating in the north, which had by now reached Thessaly. Sulla immediately marched against the united troops, and defeated them at Chaeronea and Orchomenus. This was the end of the invasion of Europe by Mithridates' armies, and Sulla, who still was involved in a civil war at home and was in a hurry, started negotiations.

At this moment, the situation became really complex. In Rome, the adherents of Sulla had suffered several setbacks, and the adherents of Marius' successor Cinna had reorganized the state. They had also sent an army against Mithridates, commanded by Lucius Valerius Flaccus and Gaius Flavius Fimbria, and Sulla wanted to receive the surrender of the king of Pontus before the latter would negotiate with Flaccus and Fimbria. Even worse (for Sulla) was that Fimbria invaded Asia itself and defeated Mithridates on the banks of the river Rhyndacus. Although beaten, the king was for some time able to play off Sulla against Fimbria, until Sulla arrived in Asia too.

In the summer of 85, Mithridates and Sulla concluded the Peace of Dardanus. The king of Pontus surrendered a part of his fleet, evacuated all conquered territories, and was forced to pay a moderate indemnity of a mere 2,000 talents. Ariobarzanes of Cappadocia and Nicomedes of Bithynia were restored. Having achieved something that was essentially nothing but an armistice, Sulla could return to Italy, where he was able to overthrow the government, become dictator, and reorganize the republic. Mithridates had survived.

The Second Mithridatic War (83-82)

The Second Mithridatic War was a brief intermezzo of the Peace of Dardanus, based on a misunderstanding. The first war had been expensive and several parts of Mithridates' empire had become restless. Therefore, the king started to recruit soldiers. The Roman governor of Asia, Lucius Licinius Murena, thought that the king wanted to avenge himself and prepared for war. He invaded Pontus but was defeated. The conflict could have escalated, but Sulla, who was now sole ruler of Rome, ordered Mithridates to desist, which he did. He had restored his prestige.

In the next years, he was able to restore his army too. He also allied himself to king Tigranes II the Great of Armenia, the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, the Roman rebel Sertorius in Hispania, Thracian tribes, and the notorious Cilician pirates. When war finally broke out, he also negotiated with the rebellious slave leader Spartacus. Moreover, his troops had been trained by a Roman officer, who had been sent to him by Sertorius.

The Third Mithridatic War (73-63)

The immediate cause of the Third Mithridatic War was the death of king Nicomedes IV Philopator of Bithynia in 75/74. In his will, he bequeathed his kingdom to the Romans. Mithridates declared this will to be a falsification, occupied Bithynia, and installed a pretender, Nicomedes IV. The Senate replied that this man was a bastard, and war was declared.

Rome was involved in several other dangerous wars (against Sertorius and Spartacus), but Mithridates had to discover that his enemies could be dangerous even when they were occupied in other theaters of war. The war was officially conducted by the Roman general Marcus Aurelius Cotta, who arrived in 73, was repelled by Mithridates, and found himself under siege at Calchedon. Far more dangerous was the governor of Asia and Cilicia, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, who easily outwitted the king at Calchedon and Cyzicus, and forced him back from Bithynia to Pontus.

The war could by now have been ended in a compromise, but Lucullus was confident that he could achieve more if he invaded Pontus, and Mithridates was confident that in Pontus, he could overcome his opponent. So in 72, the theater of war was transferred to the east. Fortress after fortress was besieged and taken by the Romans, the king had to retreat, and in 70, Lucullus had occupied all Mithridates' territories west of the river Euphrates, including Sinope, the capital of Pontus. The defeated king fled to Armenia, where he hoped to find support from his son-in-law, king Tigranes the Great.

Lucullus immediately sent envoys to ask for the king's extradition, and in the meantime reorganized the Asian provinces of the Roman empire, lowering the taxes and interest rate. This made him a lot of enemies in Rome, where many wealthy people had shares in tax-farming companies and saw their profits reduced.

When king Tigranes II the Great of Armenia refused to extradite Mithridates, Lucullus launched a bold attack on Armenia. In 69, he crossed the Euphrates, proceeded through Mesopotamia, reached the Upper Tigris valley, defeated his enemies, besieged Tigranes' capital Tigranocerta, and finally took it after what had been - in spite of the fact that Tigranes had been able to escape - one of the most brilliant campaigns in ancient history. On his return to Mesopotamia, Lucullus also took Nisibis, and in 68, he invaded eastern Armenia, where he reached Artaxata (near modern Yerevan). However, his enemies in Rome managed to secure his recall before he could achieve something.

Even worse, Mithridates had been able to return to Pontus with an army that had been given to him by Tigranes. He invaded his own country, and overcame Lucullus' deputies (67). At the same time, the Cilician Pirates were becoming increasingly dangerous towards the Romans, who decided to send their best commander, Pompey the Great, to deal with them. In a swift campaign, he overcame them, and in 66, he was allowed to finish the Third Mithridatic War as well.

He allied himself to the Parthian king Phraates III, who invaded Armenia while Pompey was invading Pontus. Mithridates was again forced to flee to Armenia, but this time, his ally was unable to help him. Pompey finally defeated Mithridates at a place named Dasteira, which was later called Nicopolis, "City of victory".

But still, Mithridates was not dispirited. Early in 65, he reached his possessions north of the Black Sea, which were governed by his son Machares. The latter was not willing to take up arms against the Romans -after all, Lucullus had recognized him- and was therefore killed by his father, who was still hoping to build an army of Scythian and Thracian horsemen, and wanted to invade Rome's possessions on the Balkans. However, his luck was now running out. His son Pharnaces revolted and gained support of the last soldiers that were loyal to Mithridates. He committed suicide, and was later buried in Sinope, the capital of the kingdom he had lost.

The three Mithridatic wars had important consequences. The eastern part of the Mediterranean world consisted of an unequal mix of Greek, Iranian, and other cultures. They could have been united in a large hellenistic empire that could rival with Rome; in fact it had been attempted before by the Seleucid kings Seleucus I Nicator and Antiochus III the Great. Mithridates was the third to try. Once his failure was understood, all countries east of the Euphrates fell to Rome: Pontus, Cilicia, the remains of the Seleucid empire, Judaea, and Crete. They became new provinces of the Roman empire, and had close ties to the center of power, being protected by powerful politicians like Sulla, Lucullus, and Pompey.