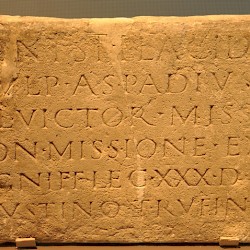

Xanten, Museum

Q316385One of the most beautiful experiences I ever had in a museum was in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome, when I saw Velasquez’ painting of pope Innocent X. There was a window in the roof, with a sheet to protect the painting from the sun, but when a cloud moved across the sky, the light in the room changed. It was as if the painting came to life.

I write this because many museums have, in the past, succeeded admirably in removing life from their objects. Shown in low key light, the artifacts look very mysterious, beautiful, and dead. My worst experience was “L’Or des Thraces” at the Musée Jacquemart-André (Paris), which offered no explanatory signs – after all, there was no light in those rooms – and instead gave its visitors small, well-written textbooks to read. So, everybody remained standing in front of the displays, trying to use the light in order to read.

The beauty of darkness is a museological cul-de-sac. People want to see objects in natural light, even if that means they are less beautiful. In the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden, the dark departments of Etruscology and Medieval History are usually empty, while you will always see people next to the Nehalennia altars, which are shown in natural light.

The new museum in Xanten has avoided the trap, maybe because the old museum was sometimes pretty dark. The new museum, on the other hand, is light and spacious; no feelings of claustrophobia here. I have the impression that this return to normalcy is part of a trend, because I noticed the same in the new museum in Tongeren.

There is a second parallel to Tongeren: both museums are really new. The people of the museum could first decide what story they wanted to tell and how they would divide it, could decide how many rooms they needed, and finally invited an architect to design the building they needed. Usually, it’s the other way round: the museum already has a building, and the available rooms determine what they can display. The new building in Xanten is essentially one very big hall, and the visitors move over several hanging platforms. This sounds more complex than it really is, but I do not know how to express this more clearly.

The important thing is, of course, that “it works”. As I already said, it is spacious and full of light. An unusually great number of artifacts can be displayed (in that sense, it is almost like a classical museum), but you have hardly the idea that there is an information overload.

What impressed me, was the great number of loans. Cooperation is now easier than it used to be, and is more or less the rule. In December 2002, the directors of the world’s major museums gathered in Munich and agreed that they ought to facilitate a lending program.

Of course I have, until now, left out the museum’s major attraction: it is in the Archaeological Park, the reconstruction of the ancient Colonia Ulpia Vetera. Until recently, it consisted of two parts: the reconstructed city and the bathhouse, with the museum as a third element, in the town itself. Now, the three have been joined. This is certainly one of the most splendid museums I have ever visited.

This museum was visited in a/o 2009.