Berg en Dal, Orientalis

Q18774131Sometimes, the history of a museum is as interesting as its collection. The Dutch Museum Orientalis in Berg en Dal (near Nijmegen) was founded almost a century ago - in 1911 to be precise - and was meant to offer a taste of the Holy Land to Christians who were unable to travel to the Levant.

It was unique. Of course, there were other living history parks, like the Pompejanum (1848), the Saalburg (1897), the Kerylos villa (1902), but these were inspired by Greece and Rome. The Holy Land Foundation, as the Dutch museum park was originally called, concentrated on Palestine. In an age in which Catholic art was inspired by the Neogothic architecture and the Beuron Art School, it was revolutionary to show Christ as a human being living in Palestine.

My parents took me to the Holy Land Foundation in the early 1970s. You could see a Jewish village with a synagogue, reconstructions of the Sanhedrin and the Palace of Pilate, Golgotha and the empty tomb. In the late afternoon, we attended a passion play. Although I was six or seven, I thought it was too pious, too devote.

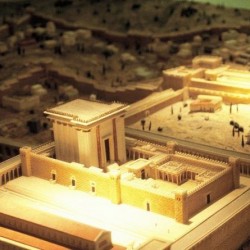

It must have been one of the last passion plays to be performed over there, because at that moment, the original museum park was already changing. It had been intended to bring people closer to Christ, and give them more love in their heart. There is nothing wrong with that. But the old kind of devotion was no longer popular. Instead, the museum started to stress the Jewish-Roman environment in which Jesus lived. For example, a nice street in Roman style was added, with exhibitions in the houses. From a visit in the 1990′s I remember beautiful models of Deir el-Medina, the Athenian Acropolis and Jerusalem.

Nowadays, the museum park is meant as a meeting place, where people can learn about the three main monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. You can see some multimedia presentations about, for instance, religious dress, food, and habits, and about more serious themes like religious hatred and religion as source for peace. The oriental landscape serves, as the museum says, as background for a “meeting of minds”.

Last Friday, I was in Nijmegen and made a walk though the park. It must have been my fourth or fifth visit. I was amazed by the high quality of the earliest reconstructions. The men who designed it, had travelled widely through the Middle East, and their Jewish village is an exact copy of a Palestine town.

Of course, we can now see that their orientalist philosophy was wrong: they believed that modern Palestine could help us understand the life of Christ, which implied that they thought that nothing had really changed over there – a rather unkind vision on the creativity and originality of the people living in Palestine. Still, their idea to put that Jew from Nazareth back in his original context, instead of reducing him to a European, artistic icon, is worth consideration, and I am glad that the old buildings are now on the Dutch Monument List.

This museum was visited in a/o 1976, 2008, 2013, 2016-2018.