Aššur

Q200200Aššur: oldest capital of Assyria, now Qal'at Šerqat.

Beginnings

Situated on a tongue of land on the west bank of the river Tigris, Aššur was the first capital of Assyria. Remains from the second half of the third millennium BCE have been found near the temple of Ištar. In this period, Aššur was still a city-state, not unlike Susa in Elam. The city was regarded as deified and the surrounding country was therefore called the Mât Aššur, the land of the god Aššur.

The city-state must have had close ties with the Sumerian city-states in the south and was subject to king Sargon of Agade and the rulers of the Third Dynasty of Ur, who sent governors to Aššur in periods in which Mesopotamia was a unified monarchy. The most important archaeological remains from this age are the temple of Ištar and the Old Palace.

When the Amorites overran southern Mesopotamia at the turn of the third/second millennium, they created the conditions for Assyria to become independent again. Aššur rapidly became an important trade center. The activities of its merchants in Anatolia are known from thousands of tablets from Kültepe (ancient Kaneš), which often mention the trade in copper, but also document many aspects of everyday life. Aššur must have become a wealthy city, was forced to build a city wall (enclosing about 56 hectares), and appears to have expanded its territory.

From a city state, the Mât Aššur was becoming a kingdom. King Šamši-Adad I (r.1813-1781?) ruled an area that included the western Zagros Mountains and a part of the land between Euphrates and Tigris. He was powerful enough to style himself "king of the universe" and displayed his wealth in the Old Palace, but his son Išme-Dagan lost his independence and became a vassal of king Hammurabi of Babylonia.

Meanwhile, the trade activity continued. Several sanctuaries that were to become very important when Assyria was an empire, like the temple of Aššur himself (the Bit Aššur or Ekur) and the city's ziggurat, date back to this period.

After a Hittite attack on Babylon and the collapse of the Babylonian Empire (usually dated to 1595 BCE), Assyria became a vassal of the kingdom of Mitanni. It seems that the double temple of the moon god Sin and the sun god Šamaš dates back to the fifteenth century BCE, but evidence is almost absent, although it is clear that several monuments were rebuilt.

Aššur, Statue of an early king |

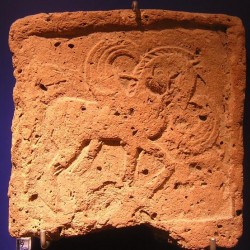

Aššur, Temple of Aššur, Old-Assyrian relief of three deities (and two goats) |

Aššur, Altar of Tikulti-Ninurta I |

Aššur, Assyrian capital |

Late Bronze and Early Iron Age

In the fourteenth century BCE, Assyria becomes "visible" again. King Aššur-Uballit I (r.c.1364-c.1328) and his Hittite colleague Šuppililiuma simultaneously attacked Mitanni, which disintegrated. The Hittites conquered northern Syria and Assyria regained its independence.

This is the beginning of the Middle Assyrian period, which saw a renewal of Assyrian expansion, especially under king Tikulti-Ninurta I (r.1243-1207). During his reign, and during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I (r.1114-1077), the city was expanded: to the 56 hectares, a lower city of 20 hectares was added. Several new monuments were built, like a second royal palace and a temple of Anu-Adad. The temple of Ištar (mentioned above), which already was a thousand years old, was rebuilt.

Tiglath-Pileser had benefited from the fact that the old Bronze Age system was collapsing. Assyria had been able to expand its power at the expense of the victims of this crisis, but after c.1075 BCE, it got its share of problems as well. Some of the western, Aramaic-speaking parts of the Assyrian kingdom became independent. For a century and a half, Assyria was in decline.

Religious Capital of a World Empire

Under king Aššurnasirpal II (r.883-859), Assyria's fortunes were restored and the kingdom again had the size it had had during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I. The expansion continued under Aššurnasirpal's son Šalmaneser III (r.858-824). However, the city of Aššur lost its political significance. The new capitals were Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Šarrukin), and Nineveh.

Aššur's religious importance, however, remained the same and the successive kings continued to build in the ancient city. The temple of Nabu, a Babylonian god, dates back to this age, and a house to celebrate the (Babylonian) Akitu festival was added as well. Several kings were buried in Aššur. It must have been a splendid place, with the northern third taken up by beautiful monuments, like the ziggurat, several temples, and two palaces.

It comes as no surprise that when Aššur was sacked by the Medes and Babylonians in 614,note it was a profound shock that may have demoralized the Assyrians. Two years later, their last capital Nineveh was captured and sacked, which meant the unexpected end of the world's first great empire.

Aššur, however, remained occupied and was destined to have a final flourishing in the Parthian age: in the first century CE, it was the seat of a semi-autonomous governor, who built a new palace and reopened the temple of Aššur. It has been argued that by now, the city had another name (Labbana or Kainai), but this has not been confirmed. After the Sasanian Persians captured the city in 241 CE, Aššur was abandoned and an urban history of almost three millennia came to an end.

Aššur, Glazed brick panel with a capricorn |

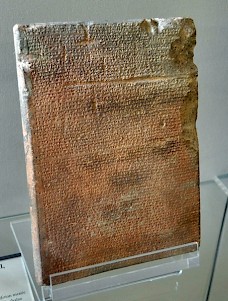

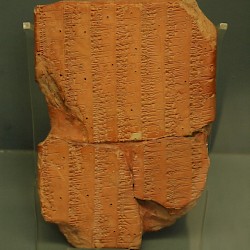

Aššur, Syllabilary with old and new cuneiform signs |

Aššur, Parthian stele of a worshipper |

Aššur, Relief of Pegasus |