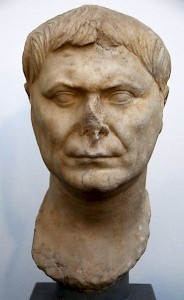

Pliny the Younger (3)

Pliny the Younger or Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (62-c.115): Roman senator, nephew of Pliny the Elder, governor of Bithynia-Pontus (109-111), author of a famous collection of letters.

After his quaestorship, Pliny proceeded to the next stage of the cursus honorum: he became tribune. Between quaestorship and tribunate, there was a statuary year's interval, and it is likely that Pliny accepted several cases in which he served as lawyer. He must have been successful. After all, he had the support of the emperor Domitian.

When he was tribune in 92, he suspended his practice in the courts. Because the tribunate was a largely honorific function, this was a remarkable sign of devotion to duty.

Domitian was impressed, and allowed Pliny to become praetor (a juridical function) without the prescribed year's interval. This was a new sign of imperial favor.

Later, Pliny would call the year of his praetorship and the following years the most difficult of his life. The emperor was a difficult man. He had always been the younger brother of the crown prince Titus, and he was unprepared when he had to succeed his brother in 81. He lacked the delicacy to deal with the Senate and wanted to be called dominus et deus, "lord and god". His autocratic behavior reminded the senators of the bad old days of Julius Caesar, Caligula, and Nero, and while the emperor was at the Danube fighting against the Dacians, the senators turned away from him.

Many returned to their country mansions, leaving the empire without experienced administrators. Others were more active. In 89, the governor of Germania Superior, Lucius Antonius Saturninus, attempted a rebellion, and in Rome, several senators with stoical sympathies seemed to think about a coup d'état. Others simply withheld information to the emperor, and, having secret agendas of their own, started to suspect the emperor of having a secret agenda as well. The emperor felt that something was seriously wrong, became suspicious and ultimately paranoid. His isolation is illustrated by his word that the fate of emperors was unhappy, since when they discovered a conspiracy, no one believed them unless they had been killed.

Pliny felt that he was in a very difficult position. Some of his friends belonged to the stoic opposition, but he himself had to serve the emperor. Things became even more difficult when the inhabitants of Baetica asked him to be their lawyer in a lawsuit against their former governor Baebius Massa, a friend of the emperor. The man was convicted, but he retaliated: he accused Pliny's colleague, Herennius Senecio, with lese majesty. The charge was not implausible, because the accused sympathized with the stoics.

At the end of 93, Domitian acted against the opposition. Herennius Senecio and several others were rounded up and killed, others were sent into exile. Besides Herennius, two of Pliny's friends were put to death, and four banished. We do not exactly know who took the initiative. It is possible that the emperor's paranoia overcame his sound judgment, but it is equally possible that factional strive in the Senate led to accusations to which the emperor ought to answer. Pliny's role in all this is almost obscure, but he did lend money to a member of the opposition, which was not entirely without danger for someone occupying an office. A decade later, he wrote:

I stood amidst the flames of thunderbolts dropping all round me, and there were certain clear indications to make me suppose a like end was awaiting me.note

But nothing happened to Pliny. He had now been praetor, which meant that he was considered to be qualified for the more important offices in the empire. With mixed feelings, he must have seen that his star was rapidly rising because of the shortage of senators (many of which had preferred voluntary exile on their country estates). In the years 94-96 he served as prefect of the military treasury. This meant that he was responsible for the pensions of the soldiers. Meanwhile, he remained on friendly terms with the members of the stoic opposition, which proves that he was either a very nice man, or was able to give this impression.

Meanwhile, Domitian's behavior became more and more erratic and dangerous. In 95, he ordered the execution of his cousin Flavius Clemens, who had, it was said, sympathized with Judaism (or Christianity?). It is likely that Domitian had in fact discovered a conspiracy, but no one believed him. A year later, there certainly was a conspiracy, and Domitian was killed. He was succeeded by Nerva.