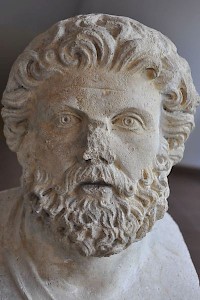

Philip II of Macedonia (6)

Philip II (*382): king of Macedonia (r.360-336), responsible for the modernization of his kingdom and its expansion into Greece, father of Alexander the Great.

After the battle Chaeronea, Philip pursued a friendly policy. He wanted to reorganize Greece, not to destroy it. What he needed was a safe southern border, so that he could leave Europe and invade the Achaemenid Empire. Besides, there was no need to attack cities and replace their governments with pro-Macedonian leaders, because they came to power almost naturally after the show of strength at Chaeronea. He only placed garrisons in Thebes and Corinth, and moved to Sparta with his army, just to impress this part of the Greek world too.

Meanwhile crown prince Alexander and the important courtier Antipater visited Athens. The envoys made the Athenians an offer they couldn't refuse: they only demanded that their defeated enemies would dismantle their empire. Because most of the Athenian allies already behaved more or less independently, this was a very moderate demand. Philip's leniency can easily be explained, because he needed the Athenian navy if he wanted to attack Persia, and he could not allow the Athenians to side with king Artaxerxes III Ochus. During the autumn of 338, Athenian representatives exchanged oaths with Alexander and Antipater.

At this moment, news arrived that the Persian king had died and was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes IV Arses. Philip knew that a Persian ruler always needed some time to secure his position, and understood that there never had been a better opportunity to invade Asia. Within a couple of months, rebellions had started in Babylonia (Nidin-Bêl), Egypt (Khababash), and Armenia (prince Artašata, who was to become king king under the name of Darius III Codomannus).

Philip immediately broke off the Spartan campaign, and invited representatives of the Greek towns to Corinth, where they organized themselves in a new alliance, the Corinthian League. Its members would remain free and autonomous, but agreed never to wage war against each other, unless it was to suppress revolution. This meant that the oligarchs that ruled most Greek towns or had recently come to power, would not have to lose their position. A Council was created that had to supervise the peace in Greece, and Philip was elected as leader (hegemon) of a common army. This office was to be reserved for the Macedonian king, and it is likely that crown prince Alexander was present too.

Having organized the Greeks in this league, Philip announced that he wanted to invade Persia, because almost a century and a half before, the Persian king Xerxes had invaded Greece and pillaged the temples of Athens. This was a pretext (if only because back then, the Macedonian king Alexander I had been Xerxes' ally), but no one really cared. There was a lot of booty to be taken away from Asia. To Philip, there was an additional bonus: no Greek would think of revolt as long as a great many compatriots were serving in the Macedonian army abroad.

The real cause of this war, of course, was not revenge, or Philip's greed, or his attempt to create peace in Greece by uniting it against a common enemy. The deepest cause was the lack of internal structure of his kingdom. As noted above, Macedonia had to expand or implode.

The moment of the invasion was well chosen. After all, the Persian king needed some time to organize his kingdom, and Artaxerxes IV Arses had to win a civil war against the rebel prince Artašata, who was marching to the south from Armenia. Besides, the supreme commander of the Persian forces in western Asia, Mentor of Rhodes, was dead too. That Artaxerxes IV was soon to be poisoned by his chiliarch (vizier) Bagoas was not yet known, but will only have improved Greek and Macedonian enthusiasm.

The invasion was to start in the spring of 336, but Philip still had to arrange a couple of things. He conducted an Illyrian campaign, and had to think about concluding a diplomatic deal with Pixodarus, the satrap of Caria. This man had opened negotiations and announced that he had a daughter of a marriable age, and Philip promised her the hand of his mentally deficient son Arridaeus. This was an important marriage, because it gave the Macedonians a chance to obtain the city of Halicarnassus, the capital of Caria and an important, heavily fortified port. During a war against Persia, this would be a first-class asset.

Unfortunately, crown prince Alexander was not happy with the deal. He thought that his father intended to appoint Arridaeus as his successor, and because he wanted to prevent this, he sent an envoy to Halicarnassus that declared that he was willing to marry the girl too. Pixodarus was delighted, but Philip was not, and ordered Alexander's advisers (Erigyius, Laomedon, Harpalus, Ptolemy, and Nearchus) to leave Macedonia.

The affair had been laid to rest, but a new and more important crisis followed when Philip announced that he wanted to marry again, with a girl named Cleopatra, the daughter of a brother of Attalus, an important courtier. During the wedding banquet, Attalus prayed that the Cleopatra might give birth to a legitimate son worthy of the throne. Queen Olympias and prince Alexander felt insulted, decided to leave Macedonia and went to the court of Olympias' brother, Alexander of Molossis.

In the winter of 337/336, this family quarrel escalated to an international crisis when Alexander allied himself to several Illyrian leaders and threatened to invade Macedonia. Now, Philip understood that things were going wrong, and he reconciled himself with his son, saying that he had sent Attalus away from court. This was true. In the spring of 336, Attalus and general Parmenion were leading the Macedonian advance force to Asia; Philip was to join them during the autumn.

When Alexander had returned, Philip decided to organize a great festival. He had to show the world that the Macedonian king and crown prince were on good terms. He also wanted to make it clear that the ties between Macedonia and Molossis had not suffered, and he therefore invited Olympias' brother, king Alexander, to come to Macedonia, and accept the hand of princess Cleopatra (not to be confused with Philip's wife). After the wedding, Philip would leave for Asia.

However, things turned out differently. The marriage took place, and there was a big festival in the theater of Aegae, but Philip was murdered by a man named Pausanias (text). He had personal motifs, but there were whispers that he was not the only conspirator. The debate about the possibility of a larger conspiracy and the names of its other members is still continuing. What is certain, is that Alexander succeeded his father and executed several opponents, that Parmenion saw to the assassination of Attalus, and that Alexander could invade Asia in the spring of 334, where he executed his father's plans.

Although archaeologists have excavated a lavishly decorated tomb at Vergina, which certainly belonged to a member of the Macedonian royal family, the identification of the buried man with Philip, is uncertain. The decoration, which shows a lion hunt, is unlikely to have been added before Alexander's eastern conquests, when this artistic motif was "discovered" by European artists.