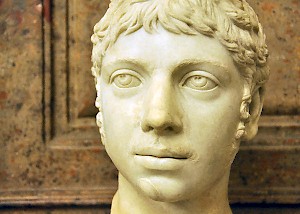

Heliogabalus (1)

Heliogabalus: emperor of Rome, ruled from 218 to 222, famous for his religious reforms and the introduction of the cult of the Syrian sun god Elagabal.

The Ancient Biographies of Heliogabalus

There are three sources that shed light on the life and opinions of Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, or, to use a well-known shorthand, Heliogabalus:

- Cassius Dio, a senator;

- Herodian, a civil servant;

- the author of the Vita Antonini Heliogabali, which is part of the Historia Augusta.

Authors of ancient historical accounts had different goals than contemporary historians. A historical account had to be more than just reliable. Entertainment was equally important, especially in the biographies of emperors. The monarch stood at the head of the Roman people and was expected to set a good example. His behavior was observed closely and his biography was in fact a moral study. Emperors such as Augustus, Vespasian, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius were depicted as wonderful men with all the virtues a true Roman should possess, such as righteousness, moderation and wisdom. Other emperors, such as Caligula, Nero, and Vitellius, were depicted as tyrants. They were scum of the earth and a scandal to the Roman throne.

The accounts of Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Vita Antonini Heliogabali share a negative view on Heliogabalus. They agree that he may have been the worst tyrant Rome had ever seen. However, the authors have a different opinion about what constituted tyrannical conduct.

Cassius Dio

Cassius Dio was a senator from Bithynia, living in the late second and early third century CE. His account (which can be read here) is written in Greek although he considered himself a Roman and his point of view is conservative, as could be expected from a senator of Rome. Dio's prose illustrates how Romans felt about Syrians, Parthians and Persians: they were perverse, superstitious, effeminate and therefore could not be seen as real men - let alone as leaders on the throne of Rome. Because of their slavishness they were only useful as servants. During the reign of Heliogabalus, Dio was not in Rome and his account was therefore based on stories that he heard afterwards. This must be kept in mind when one judges Dio's credibility, and most modern scholars agree that his account of the reign of Heliogabalus is not the best part of his Roman History.

Several aspects must be noticed while reading Cassius Dio's account. First of all, there is hardly a chronology in his narrative, with two exceptions: when he describes Heliogabalus' coup, and when he describes the fall of the emperor. On the second place, Dio's account contains much criticism. The emperor's appearance and conduct are assaulted. This is the typical approach in an emperor's biography; immoral behavior and appearance are characteristics of a bad emperor.

The emperor's cruelty is proved by naming all who had been murdered in his name. Dio also stresses the perversity and lust of the monarch. Quite remarkable is the emperor's tendency to imitate women with a special liking towards prostitutes. This effeminacy of the emperor is stressed in other passages as well. Cassius Dio is disgusted by this conduct. In his view, the boy's effeminacy proves that he was unfit to rule. Dio is also offended by the religious reforms, which resulted in a neglect of state affairs. Not only is this incomprehensible to Dio, who was proud to be a loyal servant of the state, but he is also angry because the religious reforms were violations of everything the Romans held sacred.

In a famous remark, he had said that

...our history now descends from an empire of gold to one of iron and rust, as affairs did for the Romans of that day.note

In Dio's view, the age of Heliogabalus was an age of rust, and he does not see why he should spend many words on the contents of the political agenda of an emperor whose reign needn't be taken seriously.

Herodian

Herodian was probably an equestrian, perhaps from Syria, and certainly wrote a History of the Roman Empire since Marcus Aurelius in Greek. He is a younger contemporary of Cassius Dio and was perhaps not in Rome during these events. Yet, Herodian may be the best source we have on the life of Heliogabalus, because he lacks Dio's prejudices.

First of all Herodian does not merely depict Heliogabalus as a brute. Admittedly, he speaks of Heliogabalus' effeminacy and seems to be thoroughly disgusted with the fact that Heliogabalus tended to smear cosmetics on his face. Yet the cruelty, perversity, and effeminacy of the young emperor do not dominate the account. Second of all, he is the only one who gives us information on the cultural background of Heliogabalus and also speaks of the Sol Invictus cult of which Heliogabalus was high priest. For example, Herodian describes the god's cult image.

Unfortunately Herodian also stresses the emperor's barbarian nature and compares him to the Roman people. In this aspect, Herodian shares the attitude of Cassius Dio. Nor does he have much to say about the political agenda of the emperor, or does he offer a chronology in his account.

The Vita Antonini Heliogabali

The Vita Antonini Heliogabali (which can here be found online) is a selection from the Historia Augusta, a series of biographies starting with Hadrian (r.117-138) and closing with Numerian (r.283-284). The author plays a game of hide-and-seek with his readers, pretending that collection was made by six authors who lived at the beginning of the fourth century; in fact, the sole author lived much later, when Christianity had already become the state religion.

It is believed that most of the information that was used in the biographies of the emperors Macrinus, Heliogabalus, and Severus Alexander, was derived from a collection of biographies by a senator named Marius Maximus, who lived during the reign of Severus Alexander and was a contemporary of these rulers.

However, the Vita Antonini Heliogabali appears to belong to the less unreliable parts of the Historia Augusta. Living in a Christian world, the author seems to plead for religious tolerance. He does so by showing his sympathy towards Heliogabalus' successor; Severus Alexander, who is portrayed as a good emperor who respects all gods, unlike Heliogabalus, who raises his god to a higher level and reduces the status of the other gods. The two biographies are, therefore, a diptych.

Heliogabalus is also depicted as a perverse, effeminate, cruel boy who does not care at all for state affairs but merely seeks ways to enhance his pleasures. One of the emperor's bad habits is stressed above all: his lust for luxury. No less than fifteen sections are devoted to this subject (text). Unlike Herodian and Cassius Dio, the author of the Historia Augusta does not need Heliogabalus' oriental origin to explain his despotism; the religious reforms speak for themselves and confirm the author's opinions about the emperor's cruelty, corruption, debauchery, and desire for luxury.

Still, it is possible to distinguish between a reliable and trivial part in the Vita Antonini Heliogabali. The first chapters, which offer a brief history of the emperor's reign, are more reliable than the second part, in which a mass of biographical material is presented to illustrate Heliogabalus' extravance. In the first part, however, some general points on Heliogabalus' political agenda can be discerned, which is more than we can say about Cassius Dio.