Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba

Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba: name of two Babylonian rebel kings who rose against his Persian overlord Xerxes in the summer 484 BCE.

The reconstruction of the brief reigns of Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba is not unlike a puzzle. Scholars have adduced many pieces of evidence, but it is plausible that not every item is really connected to the insurrection:

- Contemporary documents in Babylonian archives dating to the reigns of Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba;

- The division of the large satrapy of Babylonia, early in the reign of the Achaemenid king Xerxes, into two parts, which were more or less identical to Iraq and modern Syria/Israel;

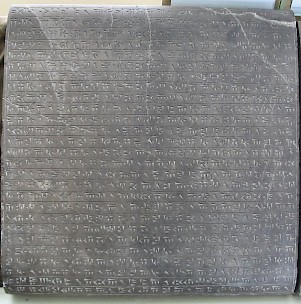

- The "daiva inscription" of Xerxes, which records the suppression of a religious revolt somewhere in the empire;

- A remark by the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus, writing about a generation after the events, that the Achaemenid king Xerxes captured Babylon and took away a statue from the main temple, the Esagila;

- A remark by the notoriously unreliable Greek historian Ctesias that there were two rebellions on two occasions; the first of these was repressed by a nobleman named Megabyzus, the second needed personal intervention by the king;

- A remark by Arrian of Nicomedia, a Roman author using fourth-century BCE sources, who states that Xerxes subdued a Babylonian revolt when he was on his way back from Greece (479). According to Arrian, Xerxes punished the city by closing the Esagila.

The best way to approach the problem is the study of the Babylonian archives, which are contemporary with the events. In the figure below, the dates and sites of the four tablets of Bêl-šimânni and the thirteen tablets of Šamaš-eriba are shown. All tablets are dated to the accession year of these kings and belong, therefore, to the same period of three months in the late summer of an unknown year after 12 April 485, because one of the tablets refers to a payment on this date.

The figure above shows that the two rebels were contemporary, but not in the same towns. Bêl-šimânni controlled the area south of Babylon; Šamaš-eriba appears to have started his reign in the north and took over the south. It is unclear what this means, but it is possible that an incident in July triggered two revolts, that one of the rebels overcame the other, and that the Persian soldiers overcame the remaining insurrectionist in October.

There is no positive evidence (e.g., a synchronism or an astronomical observation) to date the tablets to a particular year, so we must look for a year from which tablets of the late summer are missing. The following regnal years are possible: 2, 7, 9, 11, 13, 14, 18, 20.

Year #2, i.e. July-October 484, is the best candidate, because in that year, many Babylonian archives came to an abrupt end, as the figure below indicates. The archives are ordered chronologically: the age-old archives of Borsippa are shown first, younger archives are shown at the bottom.

It is unmistakable that many archives, especially the most ancient ones, come to an end in 484. In several small archives, which contain less than one tablet per year, the end comes a bit earlier, but the general impression is that something remarkable happened during Xerxes' second year.

On the other hand, it cannot be denied that several archives continued after 484. However, this in fact confirms the general picture. These are the archives of cities in the southeast that did not take part in the insurrection: Ur (Gallabu and Sin-ili; green), Uruk (Gimil-Nana; light blue), and Cutha (Bêl-uballit; grey). The other continued archives, from cities that had joined the rebellion, can be identified with people who had made their careers in Persian service. Zababa-šarra-usur, for example, was the majordomo of the estate of the crown prince.

The archives that came to an end in 484 were those of the traditional Babylonian establishment and people who had close ties to it, like the Egibi family. The end did not come completely unexpected: the owners of the terminated archives appear to have had some time to take the most precious tablets with them. In the terminated archives, we do not find property deeds.

A first possible conclusion can be that in July 484, two rebellions started. South of Babylon, Bêl-šimânni was recognized as king; Šamaš-eriba started his reign in the north but at the end of August or the beginning of September, he also gained control of the south. Perhaps one leader defeated the other, or perhaps the two rebellions merged. When the Persian forces had restored order in October, king Xerxes singled out the old Babylonian establishment for punishment, which suggests the rebellion had been religious in nature. Perhaps, he also divided the satrapy of Babylonia into two halves.

This conclusion can be supplemented by evidence from the other sources. If the Daiva inscription refers to the revolt of Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba (which is by no means certain), we have additional evidence for the religious nature of the conflict, something that may also be pointed at by the story of Herodotus that Xerxes took away a statue from the temple of Babylon.

Perhaps there is a twist. Ctesias remarks that Babylon revolted twice, and Arrian states that Xerxes captured the city when he returned from Greece. Under normal circumstances, we would ignore Ctesias, who is so often mistaken that he cannot be taken seriously. On the other hand, Arrian is not an author we can discard so easily. It is not impossible that there was after the revolt of Bêl-šimânni and Šamaš-eriba in 484, which led to the end of the archives, a second revolt took place in 479. It must be noted that Herodotus also promises to describe the origin and splendor of Babylon, for which the sack of the city would have been a perfect occasion.

This is not an academic question, because an insurrection in Xerxes' seventh regnal year would explain why the great king, after the conquest of great parts of Greece, unexpectedly disbanded his navy in the winter of 480/479. Any history of Xerxes' Greek war must take into account that Babylonia had been unquiet and probably still was; the possibility that Greece was saved by a second insurrection cannot be discarded.

Literature

- F.M.Th. de Liagre-Böhl, "Die babylonischen Prätendenten zur Zeit des Xerxes" in Bibliotheca Orientalis 19 (1962) 110-114

- R. Rollinger, Herodots babylonischer Logos. Eine kritische Untersuchung der glaubwürdigkeitsdiskussion, 1993 Innsbruck

- P. Briant, "La date des révoltes Babyloniennes contre Xerxès" in: Studia Iranica 21 (1992) 7-20

- C. Waerzeggers, "The Babylonian Revolts Against Xerxes and the "End of Archives"" in: Archiv für Orientforschung 50 (2003/2004), 150-173

Thanks to Caroline Waerzeggers.