Franks (2)

Franks (Latin: Franci): tribal federation on the north and east bank of the Lower Rhine, which created a late antique kingdom in France.

The Fourth Century

After the reign of Constantine the Great (r.306-337) the Rhineland was generally peaceful. We know of a few German incursions, including what appears to have been a large invasion in 355. The brief usurpation of one Silvanus, a high-ranking Roman officer with Frankish ancestors, and an invasion by the Alamanni, complicated the situation, but general Julian restored order.

In 357, he defeated the Alamanni near Strasbourg and in the next summer, he allowed groups of raiding Franks to settle in Toxandria. This was an agriculturally poor region to the north of the main road from Cologne to Boulogne. Various tribal brothers had already preceded them there. After all, the Franks migrated between summer and winter pastures. By the second half of the fourth century, the Franks had become the dominant group of inhabitants in Toxandria.

One piece of evidence for their settlement can be found in the large Roman mansion at Voerendaal (east of Maastricht). In the first half of the fourth century, this villa was still being fortified by its owner against German plunderers. There is evidence, however, that at a later date, the owner allowed German immigrants to build houses on his land. We can assume that, initially, these people worked as laborers. At some point, the owner left, and by the end of the fourth century, the descendants of the first immigrants moved to the main building.

The Roman government seems to have been somewhat concerned by the presence of the immigrants. In 365, marriages between the old inhabitants of the Roman provinces and people of barbarian origin were prohibited, but this statute would turn out to be a dead letter. Obviously, the Romans could do little to stem the tide of German land-seekers and usually allowed them to settle within the empire. New taxpayers were always welcome.

The usual conditions were that, in time of war, they would fight on the side of the Romans. By the end of the fourth century,most of the troops in garrison towns like Xanten or Nijmegen will have had German ancestors. Many were career soldiers, such as Arbogast, who was supreme commander of the Roman forces in western Europe between 388 and 394. These men adopted the Roman way of life, started to speak Latin, and often converted to Christianity. The Byzantine historian Zosimus calls Arbogast and his colleague Baudo "strongly attached to the Romans, free from corruption or avarice, and prudent as well as brave soldiers".note

Others, however, were less Romanized and continued to use the old German language. In this way, the Rhineland and Toxandria were lost to Latin. Thus, in the second half of the fourth century a linguistic frontier came into being. Frankish was spoken in Toxandria, whereas, south of that, Latin remained in use. This has echoed down the centuries and is the cause of the division between the Dutch-speaking Flemish and the French-speaking Walloons that exists in Belgium today.

An Age of Ambiguity

In 383, a military commander named Magnus Maximus usurped imperial powers in Britain, Gaul, and the Iberian peninsula. To strengthen his army, he bought the support of Frankish allies. This was to become standard policy: every usurper and every official emperor with ambitions in Gaul would strengthen his army by paying Frankish groups.

From treasure finds, we can deduce that the usurper Constantine III (r.407-411), the emperor Honorius (r.395-423), and the usurper Jovinus (r.411-413) hired Frankish soldiers. In 407, Frankish troops defeated the Vandals. The Roman commander Aetius received support from Frankish soldiers in his war against the Huns of Attila (451).note

There were problems as well. In c.423, Aetius had to recover Cologne and Xanten from Frankish occupiers. Merovech, who may have been the commander of the Franks fighting against Attila, was not above attacking Cologne and Mainz. At least some Franks were starting to look at themselves as independent under their own leaders.

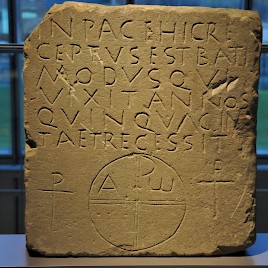

It was an age of ambiguity. A man named Chlodio succeeded in uniting some local leaders in northern Gaul under his authority and extended his power as far as the Somme.note His residence was in Camaracum, modern Cambrai, in northern France. A Frankish warrior could perhaps consider Chlodio to be king and sovereign ruler, but the emperor must have thought that he still waved the scepter in the north. The ambiguity is very nicely expressed in an inscription from Aquincum wherein someone refers to himself as Francus ego, cives Romanus, miles in armis, “I am a Frank, a Roman citizen, and a soldier in the army”.note

In the course of time, more and more Franks moved to the south. The descendants of Arbogast (above) reigned from Trier, and other Frankish leaders became masters of Cologne, Metz, and Mainz. Some groups kept their own language, but in Belgica the unavoidable happened: Chlodio’s Franks merged with the local inhabitants and started to speak Latin, the language of the Gallo-Roman population. (The proverbial lingua Franca is Latin.) Many Franks also received baptism, but it is not clear just how many.

Childeric

Merovech's son Childeric may have come to power in around 455, and was confronted by the chaos that went hand in hand with the disappearance of the Roman administrative structure from western Europe, a process that is usually referred to as the fall of the Roman Empire. Those who were holding office started states for themselves and we know from a letter that Childeric's career started as governor of the old province of Belgica Secunda.note This is the western part of modern Belgium and the northern part of modern France.

More to the south, a man named Aegidius was in control of Lugdunensis Quarta and other parts of Central Gaul. In 457, Aegidius sided with a new emperor in Italy, Majorian, who wanted to restore Roman control in Gaul. Aegidius hired Frankish allies. A treasure of coins from Lienden in the Netherlands, discovered in 2017 and dating back to the reign of Majorian, proves that Childeric paid local Frankish leaders. In other words: Childeric’s network was strengthened with money from the Late Roman network.

The murder of Majorian marked the end of Roman claims in Gaul. Still, the ties between the Franks and Aegidius had been created and in 463, Aegidius could employ Franks in a conflict with the kingdom of Tolosa in Aquitania. This post-Roman state was ruled by an elite of Visigothic descent. Although Childeric is not mentioned in our sourcs, he may have been among the Frankish warriors fighting for Aegidius.

Childeric’s presence in the south is attested in the year 464: according to the Life of Saint Genevieve, he besieged and captured Lutetia (modern Paris). He did not keep the city: after c.465, Aegidius’ son Syagrius started to push back Childeric to the north. Now an ally of a local leader named Paulus of Angers, Childeric again fought against the Kingdom of Tolosa and on another occasion, he attacked Saxon pirates in the valley of the Lower Loire.

All in all, Childeric expanded the horizon of the Franks: Central and West Gaul were now within reach. (This is confirmed by archaeology: in the second half of the fifth century, people in the country north of the Seine were increasingly often buried with a type of sword that was used by the Franks.) Roman government had collapsed and sovereignty was now in the hands of new leaders.

Childeric may have died in 481 and was buried in his residence, Tournai. Among the grave gifts – which were discovered in 1653 and stolen in1831 – was a fibula of a very rare type, used by the highest Roman officials only. Childeric was buried with his horses, which was a very German custom. His ring identified him as rex, “king”. In other words, the founder of the Merovingian dynasty and creator of the new independent kingdom was both a Roman and a German.

Scholars have argued that the sacrificed horses and the treasure of gold found with the grave prove that Childeric was a heathen, because a Christian would not have been buried with such objects. This conclusion is, however, questionable: we know of comparable burials of baptized German leaders (e.g., Sutton Hoo). Nor does the fact that the Life of Saint Genevieve ;calls him a pagan prove very much: it is just part of the portrayal of the besieger as a dangerous enemy. Nothing prevents us from accepting that Childeric was, like so many Romans of Germanic descent, a baptized Christian.

Trivières, Late Roman or Frankish helmet |

Frankish fibula from Arlon |

Frankish fibula from Arlon |

Anderlecht, Frankish Shield Boss |