Teutoburg Forest (9 CE)

Q87779Battle in the Teutoburg Forest (Latin Saltus Teutoburgiensis): the defeat of the Roman commander Publius Quintilius Varus against the Germanic tribesmen of the Cheruscian leader Arminius in 9 CE. In this battle, three legions (XVII, XVIII, XIX) were annihilated.

Introduction

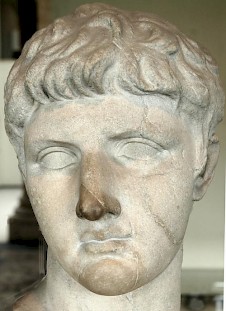

The name of the Teutoburg Forest in Germany will forever be connected to one of the most famous battles from ancient history, the clades Variana, the defeat of the Roman general Varus. In September 9 CE, a coalition of Germanic tribes, led by a nobleman named Arminius, defeated the Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth legions and forced their commander Publius Quintilius Varus to commit suicide. The result of the battle was that Germania remained independent and was never included in the Roman empire.

In the nineteenth century, the battle became a powerful national symbol. In 1806, the French army of Napoleon Bonaparte decisively beat the armies of the German states. The humiliation was too big for the Germans, who started to look to the battle in the Teutoburg Forest as their finest hour. As Napoleon spoke a romanic language and presented himself as a Roman emperor, it was easy for the Germans to remind each other that they had once before defeated the welschen Erbfeind - an untranslatable expression that refers to the Latin speaking archenemies of Germany. The Teutoburg Forest became the symbol of the eternal opposition between the overcivilised and decadent Latin and the creative and vital Germanic people, between old France and new Germany.

To make the connection between the noble savages of Antiquity and the modern nation closer, the Germanic war leader whose name had been rendered by the Romans as Arminius was referred to by his (presumed) real Germanic name: Hermann. Already famous in the days of Martin Luther, who invented the name Hermann, the Germanic leader became a very popular hero in nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Germany, and a symbol of national unity that could be used on almost any occasion. For example, in 1809, the romantic poet Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) wrote a play called Die Hermannsschlacht, to inspire the Germans to a national war against Napoleon. At Detmold, which was believed to be the site of the battle, the Hermannsdenkmal was erected in 1875. The first soccer club of nearby Bielefeld was (and is) called Arminia. The list is endless.

Arminius/Hermann was not alone. The nineteenth-century witnessed the resurrection of many ancient war leaders, who were used as a symbol by nationalists: the French exploited Vercingetorix, the Belgians Ambiorix, the Dutch Julius Civilis, and the British Boudicca. The difference is that they were all defeated by the Romans; Arminius, on the other hand, was ultimately victorious.

Although it is certainly incorrect to see the battle in the Teutoburg Forest as part of the history of an eternal, quasi-natural antithesis between France and Germany, it cannot be denied that the Roman defeat was indeed an important battle.

The Roman Conquest of Germania

In the last decade of the second century BCE, the Romans first encountered Germanic tribes. The Cimbri and Teutones were dangerous enemies, but ultimately defeated by the Roman commander Marius in two battles in 102 and 101. For two generations, all was quiet on the northern front, but in 58, when Julius Caesar was waging war in eastern Gaul, he also got involved in a war against the Germanic leader Ariovistus. At Colmar, the Roman defeated his enemy. Caesar had shown himself to be a worthy relative of Marius, and excelled himself when he bridged the Rhine and invaded the country to the east of this river, which he called Germania.

Caesar now wrote that the river Rhine was the natural boundary between the Gallic barbarians ("Celts") and the Germanic tribes, which were even more barbarous. This was nonsense. Caesar needed a well-defined theater of operations and the Rhine was, from a military point of view, a fine frontier. But from a cultural or ethnic point of view, it was not a frontier at all. The Celtic culture, called La Tène by archaeologists, could also be found on the east bank of the Rhine, and people speaking a Germanic language had already settled on the west bank.

In 39-38, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa was governor of Gaul, and fought a war on the east bank of the Rhine on behalf of the Ubians against the Suebians, a (real) Germanic tribe that was notorious for its aggressiveness. After the campaign, Agrippa resettled the Ubians on the west bank of the Rhine, and founded Cologne. The Rhine was now changing into a frontier between an increasingly Roman Gaul and an increasingly Germanic Germania. The entire area east of the great river was in a process of rapid ethnic transformation, in which entire tribes migrated to other areas - sometimes in support of the Romans (e.g., the Batavians) or to evade trouble (e.g., the Marcomanni).

During this dynamic age, the tribes of the east bank sometimes raided the Roman empire. In the winter of 17/16, the governor of Gallia Belgica, Marcus Lollius, was defeated by the Sugambri, and the Fifth legion Alaudae lost its eagle standard: the ultimate disgrace to a Roman army unit. The emperor Augustus understood that the Rhine frontier was still unstable and sent his adoptive son Drusus to the north, where they had to pacify the region and create a more stable frontier.

In the years 16-13, they reorganized the strip of land along the Rhine, which now became a military zone, where the army of Germania Inferior (XVII, XVIII, XIX) defended the Roman empire against invaders from Germania. A second army group was called the army of Germania Superior, consisted of V Alaudae and I Germanica, and was stationed along the Middle Rhine.

In 12, the Romans were ready to strike. The Sugambri knew they were doomed and decided upon a preemptive strike, but Drusus defeated them near the Rhine and in their homeland. Returning to the river, Drusus' legions were transported on ships to Nijmegen and a newly dug canal to the North Sea. Here, the Frisians and Chauci were forced into surrender. It seems that at least one military standard was returned, because a coin minted by a man named Lucius Caninius Gallus in 12-11 shows a Germanic warrior offering a standard.

Next year, Drusus again invaded the country east of the Rhine. He crossed the country of the Sugambri, proceeded along the river Lippe, reached the Cherusci, and would have crossed the river Weser if the omens had been better. On his return, he founded a large military base, which has been discovered by archaeologists near the German town Oberaden. Dendrochronologically, this site can be dated to the autumn of 11 BCE. Three legions used it as their winter quarters. A similar fort was built near Rödgen, 190 kilometers to the south.

The Lippe valley, which was rich in grain, was now pacified. Next year, Drusus and the army of Germania Superior proceeded from Mainz on the Middle Rhine to the Chatti. This campaign was repeated in 9. In the summer, Drusus reached the river Elbe. (In 2004, a fort belonging to this campaign was discovered at Hedemünden, where the Werra and Eder unite.) However, on his way back home, he fell from his horse and died. The conqueror of Germania was twenty-nine years old.

We do not know what Drusus' war aims were. It is often stated that he wanted to move the frontier from the Rhine to the Elbe, but there is no evidence for this, and it is extremely unlikely that the Romans were aware of the advantages of a frontier at the Elbe. It was only in 5 CE that the Roman legions marched along a substantial stretch of this river. Probably, Drusus was simply interested in occupying the region and exercising a loose kind of control, without bothering about the exact eastern border of the Roman empire.

He was succeeded by his brother Tiberius, a capable general who understood that Germania was too poor to be a valuable part of the empire. On the other hand, the armies could not be recalled after the death of Drusus: that would look as if the Romans had been defeated. In the years 9 and 8, Tiberius attacked the Sugambri and deported thousands of them to the west bank of the Rhine. They became known as the Cugerni and lived in farms near Xanten, where Tiberius stationed the Eighteenth legion. The soldiers of Oberaden were transferred to a new and better camp at Haltern, where the presence of the Nineteenth legion is attested. Perhaps the Seventeenth was there too.

All seemed quiet, although a Germanic insurrection is attested at the beginning of our era. A Roman army commanded by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus suppressed it and even crossed the river Elbe. In 4 CE, Augustus ordered Tiberius to go north again, to finish the conquest of Germania. The area was to become a normal, tax-paying province. The army of Germania Inferior marched from the Rhine to the sources of the Lippe, where a camp was built at Anreppen. Next year, the legions had a rendez-vous with the Roman navy at the mouth of the Elbe, and Tiberius marched along this river, which was to become the eastern frontier of the new province. (An eyewitness-account survives in the Roman History of Velleius Paterculus.)

The only part between the Elbe, Rhine and Danube that remained unconquered was the kingdom of Maroboduus, the leader of the Marcomanni, who lived in Bohemia. In the winter of 5/6, the army of Germania Superior (I Germanica and V Alaudae) marched to the east along the river Main and built a large base at Marktbreit. From here, two legions could attack Maroboduus; at the same time, Tiberius would march to the north from the Danube, where eight legions (VIII Augusta from Pannonia, XIII Gemina, XIV Gemina, XV Apollinaris and XX Valeria Victrix from Illyricum, XXI Rapax from Raetia, and XVI Gallica from Germania Superior and an unknown unit) were gathered at Bratislava. It was to be the most grandiose operation that was ever conducted by a Roman army, but a rebellion in Pannonia obstructed its execution. Tiberius was occupied for three years until he had suppressed the insurrection.

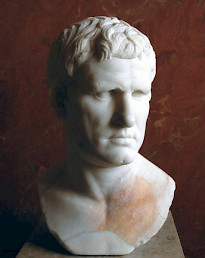

Meanwhile, the army of Germania Inferior was commanded by Publius Quinctilius Varus, one of the most important senators of his age and a personal friend of Augustus. He had to make a normal province of the country between the Lower Rhine and Lower Elbe, and had some success. Then, everything suddenly went wrong. In September 9, Varus and three legions were ambushed in the marshes of the Teutoburg Forest and massacred.