Marathon (490 BCE)

Q207250Battle of Marathon: famous clash between a Persian invasion force and an army of Athenians in 490 BCE.

In 492 BCE, the Persian king Darius I the Great decided to extend the power of his empire across the Aegean Sea, where the Yaunâ (Greeks) had been a source of trouble for some time already. General Mardonius annexed Macedonia and two years later, Datis and Artaphernes were sent out on a naval expedition to conquer the Aegean islands. After finishing this campaign, they were supposed to bring back Hippias, the former tyrant of Athens, who would set up a pro-Persian regime.

The campaign started without serious problems and soon, the islands of the Aegean Sea were subdued. To celebrate this success, the Persians sacrificed at Delos, maybe because they identified the god Apollo with their own Ahuramazda. After this, the Persian navy continued to the isle of Euboea, where the expeditionary force attacked Eretria, one of the Greek cities that had supported Greek rebels in Asia Minor. Fighting continued for six days, but the town was betrayed on the seventh day. Its inhabitants were carried off as prisoners.

The part of Athenian territory opposite Euboea - and also the best ground for cavalry to maneuver upon - was at Marathon, and it was to this village that Hippias directed Datis, Artaphernes, and the 25,000 Persians. There was a symbolic reason as well: Hippias' father Pisistratus had once landed at Marathon, and had become tyrant of Athens.

Immediately, the Athenians sent out a force of some 10,000 heavily armored infantrymen (hoplites), which blocked the road to Athens. At the same time, they sent a messenger named Pheidippides to Sparta, who returned three days later (after covering some 450 kilometer!) with the message that the Spartans would send reinforcements as soon as possible. Unfortunately, a religious law forbade any military operation until full moon, which was still six days ahead. (This full moon allows us to date the battle to 10 September or 12 August 490.)

While the Athenians postponed the engagement, they received reinforcements from their ally Plataea. The main problem for the Greeks was the superior Persian cavalry; no infantry line could cross the open plain, because its rear would be exposed to attacks by Persian mounted archers.

Among the Athenian commanders was a general named Miltiades, who had a grudge against the Persians, who had forced him out of his personal kingdom at the entrance of the Hellespont. On the day on which he was to command the Greek army, he received favorable omens and moved his army into position, allowing the center to be weak, but strengthening the wings. At dawn, he ordered his heavy armored men to run towards their enemies, about two kilometers away. The Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus, whose Histories are our main source for the events, remarks that the Persians considered this charge "suicidal madness".

On the wings the Athenians, fighting with better armor and longer spears than their enemies, routed the invaders, and after this first victorious engagement, the wings attacked the Persian center from the rear. According to Herodotus, the Athenians lost 192 men in the ensuing mêlée, their opponents 6,400.

This is exaggerated (6,400 = 192 × 100/3), but no doubt the invaders suffered heaby losses. A German officer, Hauptmann Eschenburg, who visited the site in 1884/1885, discovered huge masses of human bones, which seemed to belong to hundreds of people. The absence of a funeral monument suggests that this mass burial was done in a hurry. (That the Athenians buried the Persians was a pious act, but the Persians must have been shocked when they heard about it: it was their practice to expose the dead.)

One mystery remains: how could the Athenians cross the plain without fear for a cavalry attack? Herodotus suggests that their charge was too swift, but contradicts this when he says that the struggle was long drawn out (which means: more than two hours).

There is, however, another story about the battle of Marathon, which can be found in the biography of Miltiades by the Roman author Cornelius Nepos (first century BCE) and in the Suda, a tenth century Byzantine lexicon. According to these sources, deserters from the Persian army had come to the Athenian camp, telling that the cavalry were away.

But why? A possible explanation is that Datis and Artaphernes had become uneasy with the stalemate, had decided to leave the plain to attack the Athenian port of Phaleron, and had ordered the cavalry to embark on the transports. If this speculation is correct, the Athenians merely attacked a Persian rearguard.

Whatever the truth, it is certain that cavalry took part in the final stages of the battle, because in the Athenian building known as Stoa Poikilê was a painting of the battle that included a Persian horseman. This painting was already lost in 396 CE.note but in the Italian town Brescia, a relief can be seen that is based on it. A similar relief can be seen in Pula in Istria.

Although the battle had been won by the Athenians, this was not the end of the campaign. Most Persian soldiers were able to retreat to their ships, which brought them to Phaleron. Here, however, they saw that the Athenian army had in the meantime left Marathon and was prepared to oppose a second invasion. Understanding that it was impossible to take Athens by surprise, Datis and Artaphernes ordered the fleet to return to Asia. The captive Eretrians were deported to Mesopotamia, Hippias never returned to Athens, and the Spartans arrived too late to take part in the battle.

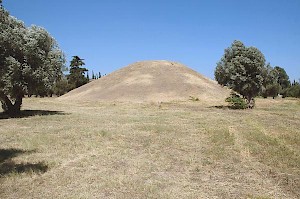

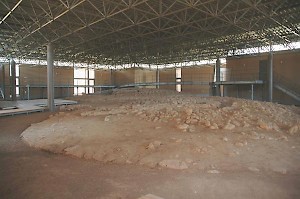

The Athenians and Plataeans received special tombs. The tumulus of the Athenians has been discovered in the middle of the plain, and the tomb of the Plataeans can be seen near the small museum of Vrana. It was unusual that Greek warriors were buried on the battlefield; the example must have been Homer's famous poem the Iliad, where we read how the heroes of the Trojan War received burials on the field. As it happened, there were ancient,Mycenaean tumuli near the battlefield, so the idea was not far-fetched. The date of the tumulus' construction is not know, but it has been argued that it belongs to the Roman age.

The well-known romantic story about the runner who came from Marathon to say that the Athenians had been victorious and died from exhaustion, is a late invention. It originates in a combination of two stories: Pheidippides' athletic achievement and the swift Athenian march from Marathon to the harbor.note

Among the Greeks who fought at Marathon was the playwright Aeschylus, who thought that the fact that he had been there was more important than all his famous tragedies, and wanted to be commemorated as Marathonomachos, not as poet. His brother was killed in action. Rumor has it that throughout the night, one can still hear horses whinnying and men fighting.