Herodotus, bk 9, logos 26

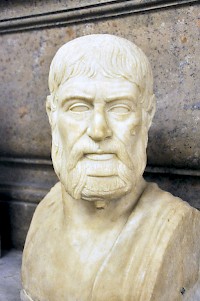

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c.480-c.429 BCE): Greek researcher, often called the world's first historian. In The Histories, he describes the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire under its kings Cyrus the Great, Cambyses, and Darius I the Great, culminating in Xerxes' expedition to Greece (480 BCE), which met with disaster in the naval engagement at Salamis and the battles at Plataea and Mycale. Herodotus' book also contains ethnographic descriptions of the peoples that the Persians have conquered, fairy tales, gossip, and legends.

The battle of Plataea (9.1-89)

When the Persian general Mardonius learns that the Athenians are not willing to come to terms, he mobilizes his army and marches to Athens. Again, the Persiand find the city deserted: its inhabitants have settled on Salamis. They send envoys to the Spartans, reproaching them for the fact that they have not come to their aid; they have to discover that the Spartans are working on the construction of the wall across the Corinthian isthmus. Only when the Spartans understand that their aloofness will force the Athenians to make common cause with the enemy and that no wall can protect the Peloponnese against a naval attack, they send an expeditionary force. Its commander is Pausanias, the son of Cleombrotus, who had died during the winter.

On hearing the news of the Spartan advance, Mardonius orders the destruction of Athens. When the old city is burning, he and his army return to the Boeotian plains. Greek soldiers from almost every city gather on the Corinthian isthmus and then march to Eleusis in the northeast, where they have a rendez-vous with the Athenian contingent. Finally, the allies move to the north, across the Kithaeron mountains, the southern border of Boeotia.

Comment

Archaeologists have been able to corroborate Herodotus' statement about the destruction of Athens by Mardonius. On the acropolis, they discovered a large depository (known as the Perserschutt), containing lots of broken and partially burnt statues - mostly representing priestesses. All of these were made in the sixth century and first decades of the fifth century. After the great fire, these sacred statues were buried on the temple domain. Other statues were taken away. When archaeologists excavated Persepolis, they discovered a marvellous statue of Penelope that was probably taken away from Greece by Mardonius (or Xerxes).

Mardonius' force was smaller than the huge army of Xerxes; consequently, it was more mobile and easier to supply. Modern historians estimate its size at 120,000 soldiers plus some 30,000 men for supply services and for the guarding of the lines of communication. It was still a large army and it could not move far from the Asopus river that divides the Boeotian plain. The Greek army counted some 100,000 soldiers; almost every Greek able to carry weapons had come Boeotia. For example, the Athenians had manned only a few galleys; all rowers and marines were now on Mount Kithaeron. This Greek army was unable to move into the plain, because they could not afford to go far beyond the sources at the foothills. After all, August can be very hot in Greece. Since no side dared to advance, a war of nerves started.

The battle of Plataea (cont.)

Herodotus describes several engagements that take place on several days. A Persian cavalry squadron tries to provoke the Greek contingent from Megara, but is defeated. After this success, the Greeks decide to leave the mountains and to descend into the plain between the river Asopus and a small town called Plataea, where a large source in the middle of the plain (near the hill in the middle of the map) will refresh them.

As usual, the Greek leaders find a cause to quarrel about: this time about the honor to fight on the left, defensive wing. The Spartans assign this responsible task to the Athenians; Pausanias rules that his countrymen will occupy the other, offensive wing. Meanwhile, the two armies refrain from attacking because they receive the same omens: they will be victorious when the other side attacks first (and moves away from its water supply).

However, Mardonius is in a hurry. His supplies are running out, he can see the Greek army growing every day and one of his advisors has already suggested to return to Thessaly and use gold and silver to bribe the Greek leaders. Mardonius will have none of it: he overrules his seers by quoting one of the responses of the Greek oracles he had consulted during the winter (above). To stop the growth of the other army, he unexpectedly and successfully attacks a large supply train in the Kithaeron. Short cavalry charges are meant to provoke his enemies into battle, but the Greeks wisely resist the temptation.

One night, the Macedonian king Alexander visits the Athenians, telling them that the Persians will attack at dawn. Immediately, the Athenian officers inform the supreme commander of the Greeks, Pausanias. He understands that if the Persians attack, it is saver to have the well trained Spartans on the defensive left wing to counter the Persian main force, and to post the experienced Athenians - already victorious at Marathon - on the offensive right wing. At dawn, the two contingents change positions, but Mardonius' spies tell him what has happened, and he changes his wings too. When Pausanias hears this, he orders his troops to go back to their original positions, a measure that is copied by Mardonius. A Persian messenger insults the Spartans: they are cowards if they leave all the fighting to the Athenians. Pausanias' men do not respond to the provocation.

In this way, the day passes without fighting, and Mardonius becomes even more anxious to attack. During the night, the Persian mounted archers attack the source between Plataea and the Asopus, hoping to force the Greek troops to go back to the south, to the sources on the slopes of the Kithaeron mountains. They stand their ground during the day - being continually harassed by Persian archers - but after sunset, they retreat to the wells.

At dawn, Mardonius learns that his opponents have fled, and thinking he has already won the battle, orders the pursuit of the Greeks. Then, he attacks the Spartans. Pausanias sends a messenger to the Athenians, who start to move from the plain immediately north of Plataea to the east, where the Spartans are under pressure. However, they are intercepted by Mardonius' Greek allies. The Spartans are in great danger, but suddenly, with the divine help of the goddess Hera, they can regroup and start to attack the Persian contingent in front of them; the latter stand their ground, until Mardonius is killed. Soon, the Persians take their heels. Their reserve, commanded by the coward Artabazus, immediately leaves the battlefield and returns to the Hellespont.

When the news of the Persian flight reaches their allies, they retreat to their camps on the boards of the Asopus. Herodotus describes the fighting in the Persian camp at great length, pointing out that the Spartans are unable to take it until the Athenians have arrived. After it has been looted and the dead have been buried, the Greek allies move north, to the city of Thebes, which had supported the Persians. After a three week's siege, the leaders of the pro-Persian party (cf. above) are handed over to the Greeks, brought to Corinth and tortured to death.

Comment

There are many strange elements in Herodotus' story. In the first place, the visit of king Alexander of Macedonia. His information led to great turmoil: the two main contingents of the Greek army have to change position. It is implausible that the king could leave the Persian camp without being seen. However, it is possible that Mardonius sent the Macedonian king, who was a loyal ally of the Persians, on his mission. It was a nice trick to create panic among the Greeks, who started all kinds of exhausting movements.

Another story that Herodotus seems to have misunderstood, was the nightly retreat of the Greeks from the middle of the plain to the sources near the foothills of the Kithaeron. This looks as if it was actually a flight for the everlasting harassment by the Persian mounted archers.

Actually, it seems as if the Persians were at first indeed victorious: the Greeks were pushed back and unable to maintain their lines of communications. Herodotus does not deny that Spartan discipline was almost breaking down and that at least one contingent of the Persian army reached the Kithaeron in its pursuit of the Greeks. The decisive moment in the battle seems to have been the death of Mardonius, who must have died as a happy man, knowing that his army had been victorious. After his death, the Spartans - nearly defeated - found new courage, regrouped, and overcame the Persians.

Herodotus' comment that Artabazus was a coward, who fled before the battle was over and went posthaste to the Hellespont is unfair. Probably, Artabazus managed to lead a large Persian contingent back under very difficult circumstances. (Herodotus' sequence of the events is confused; it is likely that Artabazus left the battlefield at a later time.) In fact, the Persian commander never crossed the Hellespont, because the Greeks had already destroyed the bridges when he arrived in Thrace. In a later section, Herodotus tells us that Artabazus' contingent crossed the Bosphorus at Byzantium. Xerxes duly rewarded him for his leadership during the Persian retreat: he was appointed satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, i.e., the northwest of what is now Turkey.

The engagement at Plataea took place in the summer of 479, perhaps in the week of August 15. It was the last battle the Greeks had to fight against the Persians at home; the next battle took place in Asia.