Herodotus, bk 2, logos 6

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c.480-c.429 BCE): Greek researcher, often called the world's first historian. In The Histories, he describes the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire under its kings Cyrus the Great, Cambyses, and Darius I the Great, culminating in Xerxes' expedition to Greece (480 BCE), which met with disaster in the naval engagement at Salamis and the battles at Plataea and Mycale. Herodotus' book also contains ethnographic descriptions of the peoples that the Persians have conquered, fairy tales, gossip, and legends.

Egyptian History (2.100-182)

The third logos of Herodotus' Histories is entirely devoted to Egyptian history. It starts with the legendary first pharaoh Min; Herodotus claims that since this legendary king 330 pharaohs have ruled.

He does not mention all of them, but gives some attention to the great conqueror Sesostris, who has conquered the whole world. The only notable fact about his successor Pheros ('pharaoh') is that he was blind. He is succeeded by Proteus, a name that Herodotus also knows from the Odyssey and allows him to digress at great length on the Trojan War and to discuss the possibility that Helen was never at Troy but remained in Egypt.

The next pharaoh is Rhampsinitus, who is so wealthy that he had to store all his wealth in a large store room. Herodotus tells us a very entertaining fairy tale about a cunning thief who managed to rob the treasury (and after all kinds of adventures marries the king's daughter and lives happily ever after).

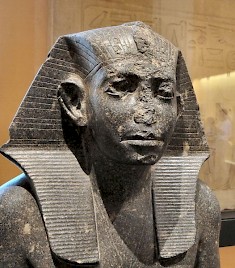

Cheops, Chephren and Mycerinus are the next kings to rule Egypt. They are credited with the building of the three pyramids at Gizeh, which are described in great detail. Herodotus claims that he has measured the pyramids personally. Another pyramid he describes is that of Asychis, the pharaoh who succeeded Mycerinus.

The blind Anysis is the next ruler of Egypt, but he loses his kingdom to the Kushite king Sabacus. After a reign of half a century, however, this man has a dream that causes him to leave the country and return it to Anysis.

His successor is the high priest Sethos, who ignores Egypt's military needs and is attacked by the Assyrian king Sennacherib. The gods intervene and ensure that mice destroy the attacking army. Having described this incident, Herodotus digresses on the antiquity of Egypt and its gods.

His next subject is the Dodecarchy, the reign of twelve rulers who divided Egypt. This experiment with collegial rule was no success, and Psammetichus reunites the country. He is supported by Greek and Carian mercenaries and succeeded by his son Necho, who conquered Gaza. His successors are Psammis and Apries, who is presented as a successful ruler who campaigned in Phoenicia.

However, his intervention in the Greek town Cyrene (in modern Libya) is unhappy and the people revolt. The new king is Amasis. He is to be the last ruler of independent Egypt.

Comment

The third Egyptian logos is a curious mixture of facts, fiction and fairy tales. Among the latter is of course the story about king Rhampsinitus and the thief. Sometimes, we can see why our Greek researcher tells a story. That Sesostris - the name of a pharaoh better known as Senusret III - was a great conqueror must be Herodotus' own invention: he tells us that Sesostris had made a monument in the neighborhood of modern Izmir in which he had written that he had met only effeminate warriors in this part of the world. In the Karabel pass, there is a monument with Hittite hieroglyphs that fits the description; since Herodotus cannot have known the difference between the hieroglyphs of the Hittites and the Egyptians, his mistake is understandable (text).

Generally speaking, Herodotus' description improves when he comes closer to his own time. He has grossly underestimated the date of the building of the pyramids, his tale about the Kushite pharaoh Sabacus already contains some elements of truth, and his narrative on the twenty-sixth or Saite dynasty (ruled 672-525) is pretty accurate. For example, Herodotus tells that these kings campaigned in the east, and we know why: to prevent a Assyrian or Babylonian attack on Egypt.

Herodotus is aware of his growing reliability and explains why: under these pharaohs, there were Greek mercenaries and merchants in Egypt, who lived in Naucratis. Culturally, these people were living between two cultures, as is illustrated by the sarcophagus of Wahibra-Emakhet.

| Greek name | Egyptian name | |

| Necho I | Mencheperra Nekau |

|

| Psammetichus | Wahibra Psamtik I |

|

| Necho II | Wehemibra Nekau |

|

| Psammis | Neferibra Psamtik II |

|

| Apries | Ha'a'ibra Wahibra |

|

| Amasis | Chenibra Amose-si-Neith |

|

| Psammenitus | Anchkaenra Psamtik III |

|