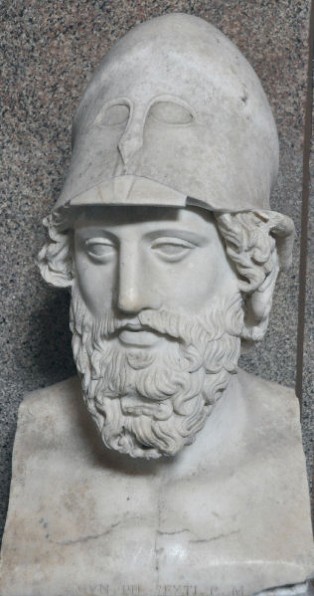

Cleon

Cleon (†422): leading Athenian democratic statesman after the death of Pericles.

New politicians

Athens had become a democracy at the end of the sixth century, but in the fifth century, it still mattered whether a politician belonged to one of the old noble families or not. Pericles, for example, was (through his mother Agariste) a member of the family of the Alcmeonids and presented himself both as a speaker in the assembly and as a general (strategos). Since the days of Homer, aristocrats had shown their care for their community during deliberations and in war, and the first democratic leaders were no exception.

Cleon was one of the "new politicians" without noble ancestors. Their wealth was not based on land, but on trade or crafts. Cleon's father Cleanetus may have been a leather merchant and tanner. An inscription lists him as a choregos, i.e., producer of stage performances. Using the money and the goodwill he had inherited from his father, Cleon started a remarkable political career as a radical democrat, claiming to be deeper in love with the people's Assembly than with his friends.

We might call him a populist, but this does not mean that he was popular with every Athenian. The historian Thucydides, who belonged to an old noble family, despised Cleon and called him "the most violent among the Athenian citizens".note In the surviving comedies of Aristophanes, the new politician is only presented in a state of anger, and when he speaks, his voice sounds like a scalded pig. However, the lack of ancestry cannot have been the only reason for the implied criticism; another new man, Nicias (who had made his fortune by hiring out slaves), is generally presented as upright, moderated, and pious.

It may be that Cleon's style was the most offensive element to the conservatives. Almost a century later, the philosopher Aristotle remembered the statesman as:

the man who, with his attacks, corrupted the Athenians more than anyone else. Although other speakers behaved decently, Cleon was the first to shout during a speech in the Assembly, use abusive language while addressing the people, and hitch up his skirts [to move about].note

This is exaggerated. It is hard to imagine that Cleon was the first to raise his voice while addressing the 6,000 people who attended the Assembly. Yet, it shows that he greatly impressed people with his histrionic performance.

Moderates and hawks

Nicias and Cleon, who were to become rivals, not only shared a common social background, they were also "hawks". In 431, the Archidamian War had broken out with Sparta and Pericles had proposed a defensive strategy. The Athenians would retire behind their long walls, and use their fleet to do damage to Sparta's allies on the coast. The Spartans would soon realize, Pericles hoped, that they had either to protect their allies and abandon the attack on Athens, or to continue the attack without support.

This was a grave error of judgment. Pericles' policy was disastrously expensive and ineffective. In the first year of war, after Attica had been ravaged by the Spartans, the Athenians attacked several cities on the Peloponnesian coast and laid waste the Megarid, but failed to achieve anything, and in the Autumn of 430, Pericles was forced out of office because he could not explain several financial matters. "The name prefixed to the accusation was Cleon," writes Plutarch,note who adds that not all historians he had consulted agreed on this name.

Pericles briefly returned to power in the spring of 429, but died soon after, and Nicias and Cleon were able to convince the Assembly that a more assertive policy was necessary. The Spartans had arrived on the same conclusion and promised help to the people of the isle of Lesbos if they would revolt against Athens, but when the islanders did so, the Spartans did not back up their promise. In 427, the Athenians had restored order and the Assembly had to decide what had to happen with the rebels of the town Mytilene.

Mytilene

It was decided that the Spartan ambassador who had informed the rebels that they would receive support, Salaethus, would immediately be put to death, without proper trial. After this, the Athenians accepted Cleon's motion to kill all men and sell their wives and children. It was a savage decree, but few people can have been surprised. The inhabitants, who had had a privileged status within the Athenian Empire, had broken their oath of loyalty, something that in Antiquity was considered to be a sin for which there was no atonement.note Worse, the Lesbians had not acted on an impulse, but had carefully planned the insurrection. The Athenians were angry and few people will have been surprised that Cleon's proposal became a law. A ship was sent to Lesbos to announce the verdict.

To their credit, the Athenians regretted their decision as cruel and excessive, and decided to reconsider it. At this point, Thucydides for the first time introduces Cleon, and makes him say that misplaced pity and a policy of leniency would be imprudent. The best way to prevent further insurrections, he argued, was a policy of deterrence. This was a complete break with the moderate policy of Pericles, which had clearly failed to keep the empire together.

Cleon's opponent was an otherwise Diodotus, who went one step beyond Cleon's arguments. Killing all Mytileneans was of course justified, he admitted, but the Assembly was not a law court where people had to decide what was just. It was a political meeting and had to be decided how Mytilene could be useful to Athens. If the Mytileneans were all killed, future rebels would fight to the bitter end, knowing that they would be killed anyhow. If the surrender of Mytilene was accepted, Diodotus pointed out, future rebels would come to terms. That would save lots of money, because siege warfare was expensive.

By a narrow margin, Diodotus won the day. Only the 'most guilty', who had already been sent to Athens, were to be executed without trial - about thousand men. This does not mean, however, that Cleon lost the debate. On this occasion, a more or less humanitarian decision had been reached, but from now on, no one would propose a moderate policy any more.

A more radical policy

No battle plan survives contact with the enemy. After four years of war, Pericles' plans had proved inadequate. In 427 and 426, the Athenians had to economize and commanders like Demosthenes, who knew how to make Athenian allies do the job, became powerful. These were difficult times for Athens, only alleviated by the fact that the Spartans weren't doing too well either.

It was in this climate that Cleon attempted to prosecute Aristophanes, who had made jokes about Athens in a play that was, after its chorus of Asian slaves, called Babylonians. In itself, this would not have been a mistake, but the comedy was shown in the presence of foreigners, who had lost their respect for the nation at war. Although the verdict of this trial is unknown, Aristophanes' comedies were no longer presented at the Dionysia, but at the Lenaea, during which no foreigners were present. Cleon appears to have won his case.

As a result, Aristophanes became one of Cleon's most ardent enemies, and it is not surprising that his comedies offer useful information about the statesman's policy. The Knights, for example, written in 425 and staged in 424, informs us that Cleon strengthened the Athenian walls by building a diateichisma, "cross-wall", but it is not clear what this can have been. The Wasps, staged in 422, suggests that Cleon had made sure that the members of the jury of the law court (heliaia) would receive three obols instead of two.

This was possible because Cleon had thoroughly reformed and improved Athenian finances. Through his agent Thoudippus, who was almost certainly his son-in-law, the tribute was reassessed. Until then, Athens had received 460 talents per year; from now on it would be three times as large. This measure has probably saved Athens, especially because Cleon had found a capable general, who was less passive than Periclean policy demanded and knew how to surprise Sparta: Demosthenes.

Pylos

In the winter of 426/425, Demosthenes had noticed that a place called Pylos could easily be fortified, and that the Athenians could use it as a base for further raids in the region. Moreover, this part of the Peloponnese, Messenia, was hostile against the Spartans, who had subdued the inhabitants, had made helots of them, and terrorized them. The Athenian garrison at Pylos offered them an opportunity to escape. This would greatly damage the Spartan economy. It was an imaginative plan, and Cleon was able to see to its financing.

When Demosthenes had landed at Pylos in the spring of 425, the Spartans immediately sent a navy, which included their future general Brasidas. They used the isle of Sphacteria as their base, and were isolated on this island when the Athenian navy defeated the Spartan ships. No less than 292 Spartan soldiers, including 120 elite Spartiates, were now cut off.

This was the most important Athenian victory during the war. Immediately, the Spartans offered a truce, because they were unwilling to sacrifice their men. They proposed a peace treaty and good will for the future, but Cleon immediately brushed it aside. There was no guarantee that the Spartans would not change their mind later. If they wanted peace, they needed to offer something better, including some sort of guarantee for future peace. The Assembly agreed and the war was resumed.

But it was a different war: it had been shown that Sparta would stop fighting when its own people were imperiled, and would betray its allies by concluding a peace treaty. Cleon had achieved a splendid diplomatic achievement. The enemy's credibility was lost, and Sparta was unable to win new allies in Greece itself.

Still, many Athenians, like Nicias, thought that Cleon had made a mistake, and he was more or less forced to promise them an even bigger victory. He went to Pylos, spoke to Demosthenes, and attacked the Spartans on the island, who in the end surrendered. This was another blow for the Spartans that sincerely handicapped them, because they could no longer attack Athens - the POWs would be executed. "Cleon's crazy-looking promise," Thucydides was forced to admit, "was fulfilled."

Although the historian presents this victory as a strike of luck, it was in fact a carefully planned operation, as we can read in the World History by Diodorus of Sicily (text). It marked the end of the myth of Spartan invincibility after its honesty had already been shown to be hypocritical.

Amphipolis

In Cleon was now at the height of his power and an infuriated Aristophanes attacked him fiercely in The Knights. Many people thought it tasteless that he devoted a comedy to blackening a war hero, and his producer Callistratus and several actors refused to work with Aristophanes, who now had to play the role of the Paphlagonian slave who manipulated his master, named Demos ('People'), himself. To make matters worse for the playwright, no artisan wanted to make a comic likeness of Cleon, so that Aristophanes had to speak his lines without mask. In spite of all this, this comedy, which remains funny, won the first prize.

Meanwhile, the Spartan general Brasidas had marched through Thessaly and was active in the north. After the Athenian victory at Pylos, invading Attica was impossible, and gaining support in Greece itself was difficult. However, the Athenian empire was still vulnerable in the north. In 424, Brasidas provoked rebellions in this area and captured the strategically important Athenian colony of Amphipolis, which ought to have been defended by Thucydides (text). On his return, Cleon charged the ill-fated commander with treason, a normal accusation levelled against failing commanders. For once, Aristophanes appears to have agreed with Cleon.note Thucydides was exiled and could start writing his History of the Peloponnesian War.

Meanwhile, both sides were wearied out by the war, and in the Athenian Assembly, more and more people were willing to listen to politicians like Nicias, who wanted peace with Sparta. Cleon was against it, but accepted that in the spring of 423, an armistice was concluded, which was to last a year. This was not the end of all hostilities, however. Scione, a town in the north that had accepted Brasidas' invitation to revolt after the armistice had come into force, was besieged by Nicias, who was unable to take it.

In 422, Cleon was elected strategos. This is remarkable. Until then, he had been a politician who left the fighting to specialized commanders like Demosthenes. This was a common division for the 'new politicians'. Now, however, Cleon acted like the traditional aristocrats, who had shown their care for the community both during deliberations and in war. Probably, he wanted to present himself in this old, respectable way to gain support from those moderates who by now preferred peace with Sparta, even though the Spartans had not offered a guarantee for future peace.

Cleon thought this was madness, and that, to continue the war, the recovery of Amphipolis was imperative. Once this part of the Athenian empire had been stabilized, the Spartans ought to be forced to make serious concessions; after that, peace was possible. So, Cleon sailed to north once the armistice was over (spring 422), and recovered several towns that had been seized by Brasidas (e.g, Torone and Galepsus). The Athenian Tribute Lists show that many other towns were brought back into the Delian League. At the same time, Cleon achieved considerable diplomatic successes by concluding alliances with king Perdiccas of Macedonia and a Thracian leader named Polles.

The main object of this campaign, however, was the recovery of Amphipolis. Cleon established his base in Eïon and waited for the Thracian and Macedonian reinforcements that he needed to besiege the city. To prepare for their arrival, he led his men out to the city, to reconnoiter the area. Brasidas understood that his position was worsening, and decided to fight a battle as soon as possible, and when the Athenians were marching back to Eïon, they were unexpectedly attacked from the city's southern gate by Brasidas and a small number of men. It was a bold maneuver, because the Athenians heavily outnumbered the Spartans. The Athenians turned to face the attack.

This slowed down their progress sufficiently to give a second Spartan army, which left the city through the northeastern gate, to catch up with the retreating force. It attacked Cleon's army from its right, where they were vulnerable (soldiers had their shields on the left arm). Both Brasidas and Cleon stood on the most dangerous positions: Brasidas led the attack from the southern gate of Amphipolis, whereas Cleon was on the unprotected wing of the Athenian army. Both commanders were killed in action.

According to Thucydides, the battle of Amphipolis removed the two men who were most opposed to peace. This is partly true. Brasidas had shown himself to be willing to break an armistice and was indeed an obstacle to peace. Cleon, on the other hand, was a democratic politician and might have followed the people's wish to look for a peace treaty, as he had done in 423, when the armistice had been concluded. Had he remained alive, peace was still possible, and probably, a treaty that had been designed by Cleon, would have been better than the treaty that was in fact signed in 421.

After the death of Cleon, negotiations were renewed. The Peace of Nicias was signed in March 421, after ten year's of war. Sparta had been unable to overthrow the Athenian empire and had lost the war, but Athens received no guarantee that Sparta would not renew its hostilities. Cleon would have demanded something like a land road to the Corinthian Gulf, so that Athens would gain control of the connection between Thebes and the Peloponnese. A peace on these terms would have been based on a realistic assessment of the political and military situation. A hypothetical "Peace of Cleon" would have prevented the renewal of the war that within three years culminated in the Battle of Mantinea.

Literature

- Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War. Athens and Sparta in Savage Conflict, 431-404 BC (2003)