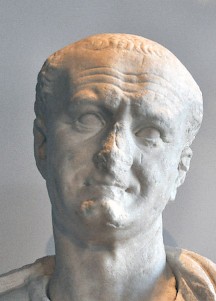

Aulus Vitellius (4)

Aulus Vitellius (15-69): Roman senator and general, emperor in the year 69.

Only a few days after he had arrived in Rome, a messenger arrived from the east, saying that the commander of the Roman forces in Judaea, Titus Flavius Vespasianus, had revolted. (He is better known under his English name Vespasian.) The governors of Egypt and Syria, Tiberius Julius Alexander and Gaius Licinius Mucianus, had already sided with him.

Vespasian was a formidable opponent. He was regarded as Rome's best military commander -he had played an important role in the conquest of Britain- and had been sent to the rebellious province of Judaea, where he had broken the back of the Jewish war. He directly controlled eight legions: his own V Macedonica, X Fretensis, and XV Apollinaris; the Egyptian legions III Cyrenaica and XXII Deiotariana; and the Syrian legions IIII Scythica, VI Ferrata, and XII Fulminata. However, he had reasons to believe that III Gallica on the Danube would also side with him.

So, Vespasian revolted. Within a few weeks, the rich provinces in modern Turkey and the eastern client kingdoms had sided with him. He decided to go to Egypt, which was Rome's main source of food; its two legions would be needed to defend the country against a naval attack by Vitellius. Vespasian left the Jewish war to his son Titus. The three legions were reinforced by XII Fulminata from Syria. Governor Mucianus of Syria was to go to the west and do the real fighting with a small army, consisting of VI Ferrata and 13,000 reconscripted veterans. Meanwhile, the navy of the Black Sea, which had sided with Vespasian as well, was to occupy Byzantium and secure the road from Asia to Europe.

Vitellius, however, was not defeated yet. III Augusta in Africa immediately sided with him. He immediately recalled the troops he had sent back to the Rhine and ordered additional recruitments in the city and among the warrior tribe of the Batavians. At the same time, a letter from Vespasian was delivered to Julius Civilis, the leader of the Batavians: both men had fought in Britain, and the new emperor requested his former ally to side with him. Civilis, however, had other reasons to fight against Vitellius. Tacitus writes:

Batavians of military age were being conscripted. The levy was by its nature a heavy burden, but it was rendered still more oppressive by the greed and profligacy of the recruiting sergeants, who called up the old and unfit in order to exact a bribe for their release, while young, good-looking lads (for children are normally quite tall among the Batavians) were dragged off to gratify their lust. This caused bitter resentment, and the ringleaders of the prearranged revolt succeeded in getting their countrymen to refuse service.note

The Batavian revolt served Vespasian's purpose of weakening Vitellius, but it would take a year to suppress it.

Being crippled by a major war in the north, Vitellius could not send an army to the Balkans: he had to wait until Vespasian's army would arrive, and he did not know where it would strike. Since his enemy possessed a navy, he could invade the "heel" of Italy; but he could also attack Italy in the north. In this difficult situation, bad news arrived: the legions of the lower Danube, VII Claudia and VIII Augusta, which had supported Otho, had followed the example of the Third legion Gallica, and sided with Vespasian. Now, Vitellius regretted that he had punished several centurions. The legions of the middle Danube, VII Galbiana and XIII Gemina, followed suit. The commander of the seventh legion, Marcus Antonius Primus, became the chief commander of Vespasian's second army.

Meanwhile, Vitellius organized games in Rome to celebrate his birthday (September). It was a way to improve the morale of the urban population, which must have been worried about the food supply. (It was to remain loyal until the bitter end.) At the same time, Vitellius started to stress the importance of unity. He accepted the name Concordia as one of his surnames and orderd coins to be minted with the legend Concordia Provinciarum, "unity of the provinces". On these coins, the goddess Concordia carried a horn of plenty, as if Vitellius wanted to reassure the people of Rome that the food supply was not really threatened. If he was hoping to prevent a civil war by this conspicuous showing of self-confidence, it was too late.

The emperor had every reason to be optimistic. Although the situation was dangerous, the army of Mucianus was still far away in the east, and the legions of the Danube that invaded Italy in the first days of September were only four in number; Vitellius, on the other hand, possessed many units of I Italica, V Alaudae, and XXI Rapax, and large parts of I Germanica, IIII Macedonica, XV Primigenia, XVI Gallica, and XXII Primigenia, and a few units of the British legions II Augusta, VIIII Hispana and XX Valeria Victrix. Besides, reinforcements were arriving, and he was recruiting a new legion (more).

In mid-September, the advance guard of the army of Antonius Primus invaded Italy. As a matter of fact, Primus' invasion of Italy was against Vespasian's orders.

His orders at this time were that the advance was to be halted at Aquileia [east of Venice] to allow Mucianus to catch up. They were reinforced by an explanation of the strategy. Now that Vespasian commanded both Egypt, with its control of the grain supply, and the revenues of the richest provinces of the empire [Asia Minor and Syria], the army of Vitellius could be forced to its knees merely by lack of pay and supplies.note

But Antonius Primus ignored his orders, and he was very lucky. When he reached Verona, the commander of the Vitellian army, Caenina, could have destroyed Primus' army before it was reinforced by the rear guard. But Caenina was contemplating to switch sides, and allowed his enemies to pass on and move to the west. When his soldiers discovered his betrayal, they arrested him and choose new commanders, Fabius Fabullus and Cassius Longus. Primus moved to the west, where two Vitellian legions were stationed. The city was to be the scene of the second battle in seven months.

The battle started place on 24 October, at about 11 o' clock. The description given by the historian Tacitus is chaotic, and we are unable to reconstruct the battle as it developed. But it is clear that the Vitellian army, which consisted of I Italica and XXI Rapax, was the first to attack, and caught the Vespasian army by surprise. However, after five hours of fighting, it was pushed back to Cremona. Now Primus told his men that the battle was over -perhaps he really believed it- and ordered them to follow the "fleeing" enemy. At sunset, the soldiers reached the Vitellian camp, and were surprised to find the two legions prepared to continue the fight. Even worse, they discovered that the Vitellian main force had almost arrived, after a march of 45 kilometers in one day.

Therefore, the Vespasians retreated and took up positions on the road to Verona. If the Vitellian army had paused and spend the night at Cremona, they could have been victorious next day. They were in the majority, and Primus' men had hardly eaten a thing. However, they lacked a commander with sufficient power, and the soldiers decided to attack during the night. At first, they were successful. But at 10 o' clock, the waning moon rose in the west. Its light fell on the Vitellians, who had to fight against people fighting from the shadow. Still, they were not defeated. Then, at 6 o' clock in the morning, the sun rose, and the Vespasian III Augusta greeted it with cheers, in accordance with a custom they had adopted in Syria.

This turned out to be the decisive moment. Both armies understood that the army of Mucianus had arrived; the Vespasians renewed the fight, and the Vitellians started to move back to their camp at Cremona. But they were not defeated yet: for several hours, they defended the camp. However, at the end of the afternoon, after a battle that had lasted 30 hours, Primus was victorious. He no longer could control his men, who continued to attack the city, which was looted for four days.

On hearing the news, Vitellius sent out his other colonel, Fabius Valens, to save what could be saved. However, he was captured by the enemy, and it was clear to everybody that Vitellius was now lost. Many provinces sided with his enemy, and he was forced to construct a line of defense in the Apennines. However, many of his soldiers went over to the other side. The last battle took place at Narnia on 17 December.

It is possible that Vitellius started to behave as a despot during the two months between the second battle of Cremona and the final Vespasian attack on Rome. If there is any historical truth to the words of Suetonius - and we may doubt this -, the following events must be dated in November.

He delighted in inflicting death and torture on anyone whatsoever and for any cause whatever, putting to death several men of rank, fellow students and comrades of his, whom he had solicited to come to court by every kind of deception, all but offering them a share in the rule. This he did in various treacherous ways, even giving poison to one of them with his own hand in a glass of cold water, for which the man had called when ill of a fever.note

(One wonders whether the man did not die of his illness.) The endgame had now started, and the older brother of Vespasian, Flavius Sabinus, convinced Vitellius that it was better to abdicate. However, the soldiers of the Rhine army and the people of Rome would have none of it, and Sabinus was forced to flee to the Capitol, where he could find refuge in one of the temples. Next day, Vespasian's son-in-law Quintus Petillius Cerialis launched the final attack on Rome, but he was beaten back by the populace of Rome, which remained loyal to their emperor.

Hurling himself recklessly on an enemy he believed beaten, Cerialis had run into a mixed Vitellian force of infantry and cavalry. The encounter took place in the suburbs, amid buildings, gardens and winding lanes familiar to the Vitellians but formidable to the enemy, who were strangers to the area. Nor did the Vespasian cavalry cooperate well [...], and the commander of one regiment, Julius Flavianus, was captured. The rest suffered ignominious rout, though the victors did not keep up the pursuit beyond Fidenae.note

This was Vitellius' last victory. He probably wanted to spare Sabinus on the Capitol, but his soldiers, hysterical, set the temple of Jupiter ablaze. Next day, Antonius Primus captured Rome (20 December). When Vitellius heard the news, he went to the palace.

Finding everything abandoned there, and that even those who were with him were stealing away, he put on a girdle filled with gold pieces and took refuge in the lodge of the door-keeper, tying a dog before the door and putting a couch and a mattress against it.

The foremost of the army had now forced their way in, and since no one opposed them, were ransacking everything in the usual way. They dragged Vitellius from his hiding-place and when they asked him his name (for they did not know him) and if he knew where Vitellius was, he attempted to escape them by a lie. Being soon recognized, he did not cease to beg that he be confined for a time, even in the prison, alleging that he had something to say of importance to the safety of Vespasian. But they bound his arms behind his back, put a noose about his neck, and dragged him with rent garments and half-naked to the Forum. All along the Sacred Way he was greeted with mockery and abuse, his head held back by the hair, as is common with criminals, and even the point of a sword placed under his chin, so that he could not look down but must let his face be seen. Some pelted him with dung and ordure, others called him incendiary and glutton [...]. At last on the Stairs of Wailing he was tortured for a long time and then dispatched and dragged off with a hook to the Tiber.note

Tacitus adds an interesting detail.

One remark of his was overheard which showed a not wholly degenerate spirit. When a tribune mocked him, he retorted "Whatever you may say, I was your emperor."note

The Vespasian army was now plundering the city. The kindness of Vitellius, who had spared the lives of the relatives of Nero, Galba, and Otho, was not among the qualities of the victors: Vitellius' brother and son were killed. His wife alone was spared and allowed to bury Rome's eighth emperor. The Senate convened and pronounced a damnatio memoriae.

The dynasty of Vespasian was to rule the empire for twenty-six years, and its official propaganda was accepted by later historians, and Vitellius' reputation was soiled, stained, and blackened. And that is a pity. He was not a saint, but he certainly deserved better.