Sextus Varius Marcellus

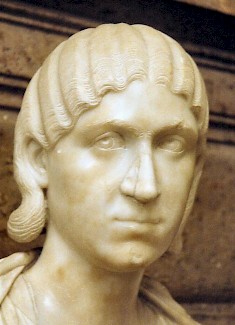

Sextus Varius Marcellus (c.165-c.215): Roman aristocrat from Apamea in Syria, husband of Julia Soaemias, father of the Roman emperor Heliogabalus (218-222).

Sextus Varius Marcellus was born in Apamea on the Orontes in Syria; in c.193, he married to Julia Soaemias, daughter of Julius Avitus Alexianus and Julia Maesa. Unfortunately, we do not know the exact date of their wedding, because their union may have been part of a larger political game. In 193, Soaemias' uncle Septimius Severus had unexpectedly become emperor, and was waging war against a Syrian rival named Pescennius Niger. The wedding of Soaemias to a Syrian may have strengthened Severus' position in the east. Unfortunately, it may as well have taken place in 192 or 194.

However this may be, the couple had a son, born in 203 and named after his mother's father: Avitus. (This suggests the existence of an older brother, named after his father's father.) The family lived in Rome, where they are known to have been present during the Secular Games of 204.

In 218, after the reigns of Severus, Caracalla, and the usurper Macrinus, the young man was proclaimed emperor by soldiers of the Third Legion Gallica (in Syria). Behind his coup were his mother and his grandmother Maesa, the sister of Severus' wife Julia Domna (cf. this family tree). As emperor, Avitus is usually called Heliogabalus, after the deity he worshiped, the Emesene sun god Elagabal.

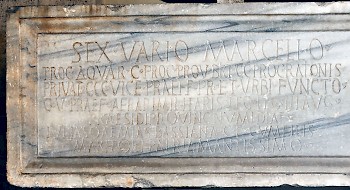

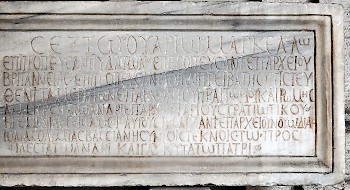

One person is missing in the story of Heliogabalus' accession: his father, who was probably dead. His tombstone, dedicated by Soaemias and her sons, has been found in Velletri, not far from Rome. It is interesting, because it proves, in the first place, that Heliogabalus had a brother: the boy named after his father's father, whose existence we already assumed. The inscription also tells us something about Sextus Varius Marcellus' career, which was remarkably unsuccessful, even though he had extremely responsible tasks.

The explanation of this paradox is that his career was blocked. Severus' powerful praetorian prefect, Plautianus, tried to obstruct the rise of other influential aristocrats and deliberately kept them out of office. (Varius Marcellus' father-in-law Avitus Alexianus is another example.) Once Plautianus had been killed, in 205, things changed.

Varius Marcellus' first task was procurator of the water supply of Rome, which meant that he was responsible for the aqueducts. It was a normal job for a man who did not belong to Rome's senatorial elite, but belonged to the second tier of the upper class, the equestrian order. It was also a beginner's function, which paid 100,000 sesterces per year, something recorded in the inscription, which mentions that he was a procurator centenarius.

He must have done his job well, because his next office was procurator of Britain, which meant that he had to gather the taxes of that part of the Roman Empire. The remarkable point is that Britain was, from 208 to 211, a war zone: Severus was trying to conquer Scotland. The emperor must have trusted Varius Marcellus. He also got a raise: he was now a procurator ducenarius, earning 200,000 sesterces.

In his third office, Varius Marcellus earned 300,000 sesterces: he was now in charge of the private finances of the emperor. In this capacity, he must have witnessed the transfer of power from Severus to his sons Caracalla and Geta, in February 211.

The two brothers hated each other, and before the year was out, Caracalla had killed Geta (December 211). This was a serious crisis, and Caracalla did not trust the praetorian prefect and the praefectus urbi. Varius Marcellus briefly took over both positions, and was, after this, admitted into the Senate, with the rank of a former praetor. Almost immediately, he was made prefect of the military treasury, which is interesting, because in 212, Caracalla gave the Roman citizenship to all free male inhabitants of the Empire, and one of the consequences of this measure was that they all had to pay the 5% inheritance tax, which was used to pay the pensions of the legionaries.

The last function mentioned on the tombstone is the governorship of Numidia, which was not normally one's last job. He must therefore have died in Numidia, or immediately after his return, before he could have reached the consulship and before Caracalla died - otherwise we would have read something about his relation to Macrinus. Sextus Varius Marcellus had occupied extremely important positions, but died before his merits had been duly rewarded.

The tombstone of Sextus Varius Marcellus, known to scholars as CIL 10.6569, can be found in the Octagonal Court of the Vatican Museums.

Literature

H. Halfmann, "Zwei syrische Verwandte des severischen Kaiserhauses", in: Chiron 12 (1982) 217-235