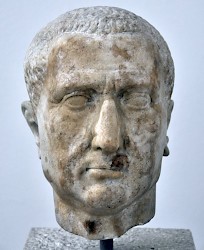

Livy

Titus Livius or Livy (59 BCE - 17 CE): Roman historian, author of the authorized version of the history of the Roman republic.

Life

The life of Titus Livius (or Livy, to use his more common English name), is not well known. Almost everything we know about the author of the voluminous History of Rome from its foundation is derived from a handful of anecdotes recorded by later authors, who may have found them in a (now lost) book by the Roman biographer Suetonius called Historians and philosophers. Nevertheless, we know something about Livy's life, and that is more than we can say about several other important ancient authors (e.g., Homer).

The Christian author Jerome, an excellent chronographer, states that Livy was born in 59 BCE and died in 17 CE. There is no evidence to contradict this piece of information. It makes Livy a near contemporary of the Roman politician Octavian, who was born in 63, became sole ruler of the Roman empire in 31, accepted the surname Augustus in 27, and died in 14 CE.

That Livy was born in Patavium (modern Padua) is clear from his own work. The historian Pollio mocked Livy's Patavian accent.

We know nothing about his parents. Several inscriptions from Padua mention members of the Livius family, but none of them can convincingly be connected to the historian. However, we can be confident that he belonged to the provincial elite and that his family, although not very rich, had enough money to send him to competent teachers. On the other hand, Livy's difficulties with the Greek language make it clear that he did not enjoy higher education in, say, Athens, which a Roman boy from the richest families certainly would have visited. The History of Rome from its Foundation offers no indication that he ever traveled to Greece.

Padua belonged to a province of the Roman empire that was known as Gallia Cisalpina. During Livy's youth, its governor was Julius Caesar, and it is likely that the boy often heard stories about the wars in Gaul. However, he never got used to military matters. His writings betray that he knew next to nothing about warfare. This, and his lack of political experience, would normally have disqualified Livy as a historian, but as we will see, he was able to write a very acceptable history.

When he was about ten years old, civil war broke out between Caesar and Pompey the Great. It was decided in 48 during the battle of Pharsalus. Later, Livy recalled a miraculous incident. His own description is not known, but a century later, the Greek author Plutarch of Chaeronea retold the story:

At Patavium, there was a well-known prophet called Gaius Cornelius, who was a fellow-citizen and acquaintance of Livy the historian. On the day of the battle this man happened to be sitting at his prophetic work and first, according to Livy, he realized that the battle was taking place at that very moment and said to those who were present that now was the time when matters were being decided and now the troops were going into action; then he had a second look and, when he had examined the signs, he jumped up in a kind of ecstasy and cried out: 'Caesar, the victory is yours!' Those who were standing by were amazed at him, but he took the garland from his head and solemnly swore that he would not wear it again until facts had proved that his arts had revealed the truth to him. Livy, certainly, is most emphatic that this really happened.note

There is another story about his youth. The Roman philosopher Seneca tells that when Livy was a young man, he wrote philosophical essays. It may be true, although Livy's writings do not betray a profoundly philosophical mind. However this may be, anecdotes like these give us the impression that the future historian was a serious young man, and this is also the impression one gets from his writings. He lacks irony and humor. On the other hand, he shows a great understanding of human psychology and has great sympathy with suffering people. We may find his gravity and earnestness a bit hard to stomach, but Livy had a heart.

After the violent death of Julius Caesar, a new round of civil war followed. Padua played a minor role and it is possible that the young Livy witnessed some of the fighting in 44/43. In 31, Caesar's adopted son Octavian was victorious, and many people had a feeling that now, after eighteen years of fratricide, the situation in Italy would normalize. Academic studies were resumed. The poet Virgil wrote his optimistic Georgics and Greek authors like Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Strabo of Amasia came to the capital. Livy seems to have shared in this mood, and published the first five books of his History of Rome from its foundation between 27 and 25.

By now, he was in his early thirties. We don't know anything about Livy's private life, but an average Roman man would at this age be married and have children. Quintilian states that the historian had a son, for whom he wrote a treatise on style, and a daughter, who was married to a teacher of oratory named Lucius Magius. Pliny the Elder quotes a geographical work written by a son of Livy.

The History of Rome from its foundation was meant as an example to the Romans. They had suffered, but that had been due to their own, immoral behavior. However, a moral revival was still possible, and Livy offered some uplifting and cautionary tales. It was a serious and important project, and Augustus was interested in it. Livy did not belong to the inner circle of Rome's first emperor, nor was he a protégé of Maecenas, but the historian and the emperor respected each other and we know that Augustus once (perhaps after the publication of Books 91-105) made a good-natured joke that Livy still was a supporter of Pompey, the enemy of Caesar. If this was a reproach at all, it was not serious. Livy remained close enough to the imperial court to encourage the young prince Claudius to write history. (The future emperor became a productive author: his histories of Rome, Carthage and the Etruscans consisted of sixty-nine books.)

Until Livy's death, he wrote on his History of Rome from its foundation. We do not know its publishing history, but the following is a plausible reconstruction:

| 26 BCE |

|

Early history |

| 24 |

|

Conquest of Italy |

| 19 |

|

Wars against Carthage |

| 14 |

|

Wars in the eastern Mediterranean |

| 11 |

|

Destruction of Greece and Carthage |

| 1 BCE |

|

The Gracchi, Marius, Cinna, and Sulla |

| 5 CE |

|

Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar |

| 8 |

|

Caesar becomes sole ruler |

| 10 |

|

War of Mutina |

| 14 |

|

Wars of the triumvirs and fall of Mark Antony |

| 17 |

|

Reign of Augustus |

He became a well-known person, and there is a famous anecdote, told by Pliny the Younger, that once, a man came all the way from Cadiz in Andalusia, from the legendary edges of the earth, to see the historian. Yet, Livy was not a very popular man. There were, it is said, never many visitors when he recited from his work. Compared to his more popular contemporary, the elegant poet Ovid, the serious historian from Padua lacked charm, irony, and other cosmopolitan qualities. His world view never was that of the Roman literary elite; he always remained a provincial. It comes as no surprise that Livy probably died at Padua.

It is possible that Livy owned a house somewhere to the northeast of Rome, because he gives remarkably accurate descriptions of the valley of the river Anio.