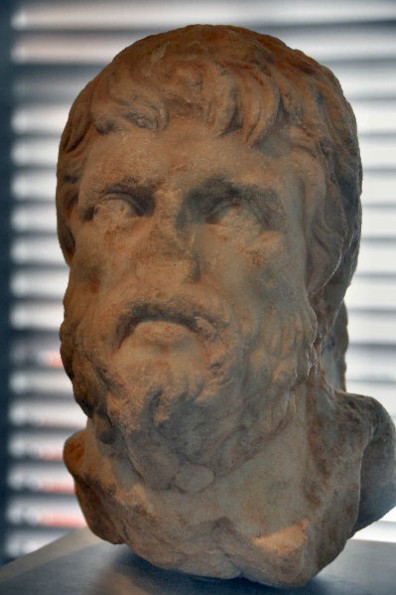

Cyrus the Younger

Cyrus (Old Persian Kurush): Persian prince (424/423-401), revolted against his brother, king Artaxerxes II Mnemon. He was defeated and killed at Cunaxa.

Cyrus was born (in Susa?) in 424 or 423, as the second son of king Darius II Nothus and his wife Parysatis. He was the younger brother of Artaxerxes II. His mother had great plans with the boy, who may have been more talented and energetic than his older brother, the crown prince. The fact that the boy had the same name as the founder of the Achaemenid empire, Cyrus the Great, may have done something to heighten his self-esteem.

In 408 or 407, queen Parysatis secured the young man's appointment as satrap of Lydia, Cappadocia and Phrygia (all in western Turkey). At the same time, he was appointed as commander in chief of Asia Minor. It was not unusual for an important Persian to rule two satrapies, but three was exceptional, and the more so because Cyrus was only 15-17 years old.

His military command was not a sine cure. At that moment, the Greek cities Athens and Sparta were fighting the last phase of the Peloponnesian War (427-404), which is usually called the Decelean or Ionian War (413-404). Both sides had made overtures towards the Persians, and king Darius had sided with the Spartans. Cyrus was responsible for the implementation of this policy. Another military activity was the war against the Cadusians, a tribe in northwest Iran (406).

Cyrus' father died in April 404, and the prince was present when his brother Artaxerxes was inaugurated at Pasargadae, the religious capital of the Achaemenid empire. Our Greek sources (Ctesias' History of the Persians, Xenophon's Anabasis and Plutarch's Life of Artaxerxes) tell us that the satrap of Caria, Tissaphernes, informed the new king that Cyrus wanted to dethrone him. We do not know whether Tissaphernes spoke the truth, but Xenophon, who did not like the Persian nobleman, does not plainly say that he was speaking outright lies. Probably, even Xenophon believed that there was some truth in the accusations. On the other hand, Tissaphernes had been succeeded as satrap of rich Lydia by Cyrus and was now ruling a poorer part of the empire; he had an ax to grind with the young prince. However this may be, Cyrus was pardoned after an intervention by his mother.

Perhaps because he had been humiliated, but probably because he had planned it all along, Cyrus decided to revolt. He started to recruit an army, saying that he wanted to attack the Pisidians, a mountain tribe in southern Turkey. Tissaphernes, noting that the army was too large for this purpose, understood the real aim of the expedition and informed Artaxerxes, who started his own preparations. Meanwhile, Cyrus tried to find political support, which he found on several places. Sparta allowed volunteers to join the expedition, and the Persian vassal king of Cilicia paid money.

In 401, Cyrus' army was ready. Its backbone was a division of 14,000 Greek mercenaries, commanded by the Spartan Clearchus. The Athenian Xenophon had a minor position; later, he was to become the commander of the rearguard. He wrote a book about the expedition, the Anabasis. This is our most important source.

After an uneventful march through Lydia, Phrygia and Cappadocia, the army reached Cilicia, where they received support from the local leader, the Syennesis, who paid the Greek soldier's wages. Nonetheless, the mercenaries revolted. They were beginning to suspect that the real aim of the campaign was Persia, not Pisidia. However, Cyrus convinced them that he needed their help for a war against his personal enemy Abrocomas. The payment of the soldiers was raised, and the army continued its march, supplemented with a Spartan contingent that had arrived by ship. Its strength may have been 30,000 men, including 14,000 Greeks.

Cyrus had expected that his enemies would sent troops to guard the Syrian gate, a narrow pass between Cilicia and the Euphrates valley. Abrocomas had indeed plans to defend it, but arrived too late. Cyrus now advanced to a place that Xenophon calls Thapsacus, where the Euphrates was fordable. (In fact, the real name Tipsah means "ford".) Here, Cyrus finally explained that he was marching to Babylon, which he hoped would come over to his side, after which he could advance to Persia proper. He announced that the soldiers would receive huge rewards when they were successful.

The march along the Euphrates was difficult, because Artaxerxes had ordered the destruction of all farms. Finally, Cyrus' army encountered the 60,000 soldiers of Artaxerxes. Xenophon states that it was some 60 kilometers north of Babylon, Plutarch thinks it was 85 kilometers. He calls the place Cunaxa. It has been identified with Tell Kuneise, west of Baghdad.

According to Xenophon, the Greek troops on Cyrus' right wing were successful. They defeated their opponents, among which were the cavalry of Tissaphernes, Egyptians and archers. At the same time, Artaxerxes' own right wing tried to wheel around Cyrus' smaller army. Therefore, Cyrus (who had already killed the commander of Artaxerxes' Cadusian cavalry in a duel) directed his own left wing against the army of his brother. This created a gap in his battle array; Tissaphernes, whose men stood between Artaxerxes and the Egyptians, broke through it and attacked Cyrus' camp.

At this moment, Cyrus and Artaxerxes were facing each other. Plutarch quotes Ctesias, who was an eyewitness.

Cyrus rode up against the king, as he did against him, neither exchanging a word with the other. But Ariaeus, Cyrus' friend, was the first to dart at the king, although he did not wound him. Then the king cast his spear at his brother, but missed him, though he both hit and killed Satiphernes, a nobleman and Cyrus' faithful friend. Then Cyrus directed his spear against the king, and through his armor pierced his breast, five centimeters deep, so that the king fell from his horse. Those who attended him were put to flight and disorder. The king and others, among whom was Ctesias, made his way to a little hill not far off. There, he tried to recuperate.Cyrus was carried off a great way by the wildness of his horse. The darkness which was now coming on made it hard for his followers to find him. However, he was elate with victory and full of confidence and force. He passed through his enemies, crying out, and that more than once, in the Persian language, "Clear the way, villains, clear the way!" They did as they were ordered, throwing themselves down at his feet.

But his tiara [the royal cap] dropped off his head, and a young Persian named Mithridates struck a dart into one of his temples near his eye, not knowing who his opponent was. So much blood gushed out of the wound that Cyrus, swooning and senseless, fell off his horse.

As Cyrus slowly began to come to himself, some eunuchs who were present tried to put him on another horse, and so convey him away safely. Because he was unable to ride, he desired to walk on his feet, and the eunuchs led and supported him. He was dizzy in the head and reeling, but convinced that he had been victorious. Everywhere he heard the fugitives saluting him as king, and praying for grace and mercy.

In the meantime, some wretched, poverty-stricken Caunians, who in some pitiful employment as camp followers had accompanied the king's army, by chance joined these attendants of Cyrus, supposing them to be of their own party. But when they made out that the coats over their breastplates were red, whereas all the king's people wore white ones, they knew that they were enemies. One of them, therefore, not dreaming that it was Cyrus, ventured to strike him behind with a dart. The vein under the knee was cut open, Cyrus fell, struck his wounded temple against a stone, and died.note

This was the end of Cyrus. His brother continued to reign until the spring of 358, but had to accept the loss of Egypt, which had become independent during the Persian civil war under pharaoh, named Amyrtaeus. The Greek mercenaries who had supported Cyrus, were forced to fight their way back through Mesopotamia and Armenia. Of the 14,000 who had left, only 6,000 returned.