Etruscans

Q17161Etruscans: ancient nation, living in the first millennium BCE in the area between the rivers Tiber and Arno.

Origin

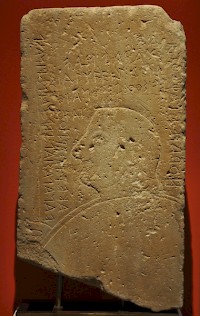

One of the most famous stories about the ancient Etruscans is told by the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus (fifth century BCE), who explains that the Etruscans migrated from Lydia to Italy.note His contemporary Hellanicus thought the Etruscans originally were Pelasgians, the legendary nation that lived in Greece before the arrival of the Greeks.note A late fourth-century BCE writer, Anticleides, agreed: the Etruscans had once lived on the isles Lemnos and Imbros, and later sailed away to Italy.note As it happens, there is a sixth-century BCE inscription from Lemnos that is written in a poorly understood language resembling Etruscan.

Writing at the beginning of our era, Dionysius of Halicarnassus states that the Etruscans

migrated from nowhere else, but was native to the country, since it is found to be a very ancient nation and to agree with no other either in its language or in its manner of living.note

This ancient debate has been continued until the present day because there is indeed something remarkable with the Etruscans: their language is different from the languages of their neighbors, but the Italian languages in the south and the Celtic languages in the north resemble each other. The Etruscan language interrupts a language continuum and it is tempting to accept that some people have indeed migrated to Italy.

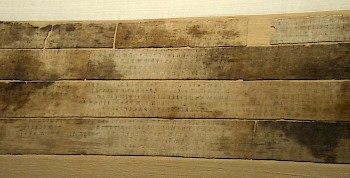

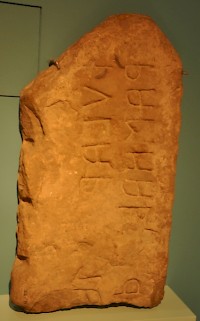

Unfortunately, the Etruscan language, which is known from more than 9,000 texts, is badly understood. We can read them - the Etruscan alphabet has no mysteries - and we understand the meaning of many simple inscriptions, but we cannot comprehend the language itself. It does not help that almost all texts are very short. The exeption is the "Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis": the text of a linen book from the third century BCE, once reused to wrap a mummy, and still very poorly understood (although it seems to be a religious calendar). There are a few bilingues, like the gold tablets from Pyrgi, but the translations are often quite free. So far, Etruscan appears to be unrelated to any other language: it does not resemble the neighboring Italian or Celtic languages, while scholars disagree about parallels in the Anatolian languages.

Meanwhile, the archaeological evidence tells a different story: in the mid-ninth century BCE, we can see the rise of the Villanova culture, which is clearly the material culture of the Etruscans. The Villanova people exported several types of metal (silver, copper, iron, lead, zinc, and tin) to Greece and also traded with the people of the Hallstatt Culture north of the Alps. This created considerable wealth and would shape society. It is very well possible that at some point, a group of foreign settlers took control of the metal mines and the trade network.

Villanova armor |

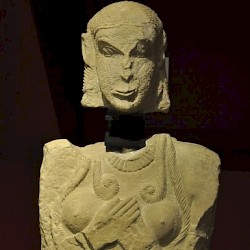

Figurine of an Etruscan warrior |

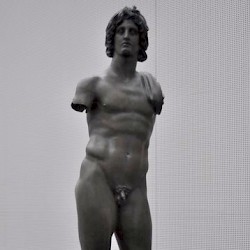

Statue of an Etruscan warrior |

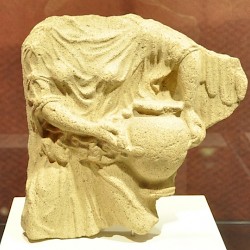

Chiusi, Model of a chariot |

Early History

The Villanova age, which began in the ninth century, is different from the preceding period because there was a recognizable growth of population. While many old hilltop villages continued, there were many new ones too. The people were living in small, hut-like houses; the dead were cremated (and buried in hut-shaped urns) or buried. From this early age on, Etruscan society was quite prosperous.

Their land bears every crop, and from the intensive cultivation of it they enjoy no lack of fruits, not only sufficient for their sustenance but contributing to abundant enjoyment and luxury.note

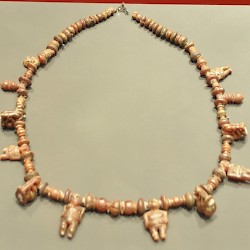

We also learn about salt works (salinae) along the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea and the exploitation of forests.note The main source of wealth, however, was the metal already mentioned above. Already in the eighth century BCE, the Etruscans were an important node in a trade network: in exchange for metal, the Etruscans received wine from Euboea. In the seventh century, the trade network expanded: we see amber from the Baltic and precious objects from Phoenicia. At the beginning of the sixth century, the Etruscans had also reached Catalonia and Andalusia.

Consequently, the egalitarian society became more stratified: an Etruscan aristocracy was created, in which power was yielded by a limited number of rich families living in splendid houses. Their members were buried in monumental tombs; among the grave gifts are locally produced wine and olive oil together with perfumes and imported objects. Wall paintings in these tombs show Greek-style banquets. Some of these monumental tombs, dating back to the seventh century, can be seen in the Banditaccia Necropolis near Cerveteri (ancient Caere).

Caere, Banditaccia necropolis, Tholos tomb |

Caere, Banditaccia necropolis, Cippus tomb |

Caere, Tomba della Capanna |

Caere, Banditaccia necropolis, Tumulus tomb |

Division and Unity

It would seem that from the late seventh century on, a new class of merchants and artisans started to grow. The villages became real towns; the towns became city-states, which were the dominant factor in Etruscan politics. It is often claimed that Etruria was a confederation of twelve city-states, but if this confederation really existed, it cannot have been much more than a very informal, religious organization.

| Latin name | Etruscan name | Modern name |

| Veii | Vei | Isola Farnese |

| Caere | Cisra | Cerveteri |

| Tarquinii | Tarchna or Tarchuna | Tarquinia |

| Vulci | Velcha | Vulci |

| Volsinii | Velzna | Orvieto |

| Vetulonia | Vatluna | Vetulonia |

| Populonia | Fufluna or Pupluna | Populonia |

| Clusium | Camars or Clevsin | Chiusi |

| Perusia | Phersna | Perugia |

| Cortona | Curtun | Cortona |

| Arretium | ? | Arezzo |

| Faesulae | Vipsul or Visul | Fiesole |

Although the Etruscans were divided into several city-states and their confederation was not really powerful, they could unite for certain purposes. According to Herodotus, the Etruscans and Carthaginians joined forces to keep the Greeks away from Corsica (Battle of Alalia, c. 540 BCE).note This presupposes the cooperation of at least some of the Etruscan cities. The same can be said about the gradual expansion to the north, to the plain of the Po. Meanwhile, individual Etruscan condottieri managed to seize power in nearby cities like Rome (Tarquinius Priscus) but they could also be expelled (Tarquinius Superbus).

In the early fifth century, there were Etruscan expeditions to the Greek towns in the deep south, which betray a substantial organization. The Greeks invoked help from the tyrant Hiero of Syracuse, who indeed offered help and put an end to the Etruscan aggression in the Battle of Cumae in 474 BCE. Syracuse now appears to have allied itself to Populonia in northern Etrusria; the southern cities of Caere, Tarquinii, and Vulci seem to have suffered.

The Rise of Rome

The fourth century started with the capture of Veii, the southernmost of the Etruscan cities, by the Roman commander Marcus Furius Camillus (in 396, according to the Varronian chronology). The neighboring towns Falerii, Sutrium, and Nepe were next, and because Rome founded colonies over there, it was clear that Rome had greater ambitions. An age of war was beginning, and the people knew it: many towns (re)built their walls in the first half of the fourth century (including Rome).

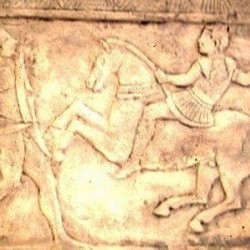

Against the new enemy, the Etruscans were divided. Cities like Caere collaborated with Rome, while Tarquinii waged war (358-351 Varronian). On other occasions, Rome interfered in local politics: for instance, in 302, it supported the aristocrats of Arretium against their serfs. All in all, Roman influence grew. After the Battle of Sentinum in 295 BCE, in which the Romans overcame several Etruscan cities and their Celtic allies, the subjection of Etruria was a matter of time.

By the end of the third century, when Rome was involved in the Second Punic War, the Etruscan towns supported the Romans. We read about Etruscan leaders who play a role in Roman politics, and after the Social War (90-88 BCE), Roman citizenship was awarded to the Etruscans, marking the beginning of a new phase of Italian history.

Caere, Banditaccia necropolis, Wall painting of an archer |

Helmet from Central Italy |

Chiusi, Helmet (Celtic type) |

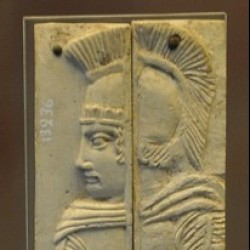

Tombstone with an Etruscan and a Celtic warrior (cast) |

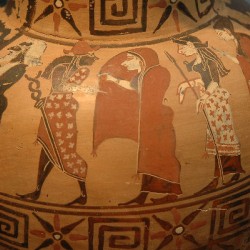

Pottery

Note: Much pottery found in Etruscan tombs was imported from Greece and other countries, so it is hard to label this "Etruscan" pottery.

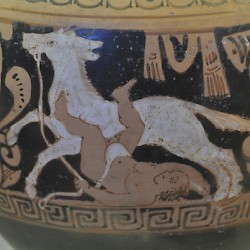

Religion

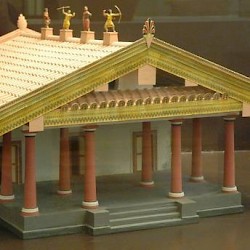

Etruscan temple, Model |

Charun |

Veii, Head of Aplu |

Caere, Etruscan antefix (silenus) |