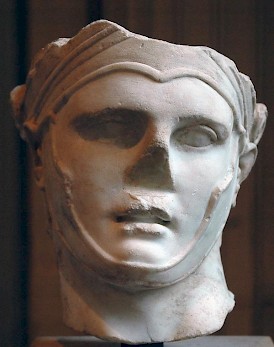

Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus (319/318-272): king of Epirus (r.306-302 and 297-272) and Macedonia (r.288-284 and 273-272), well-known for his war against the Romans (280-275).

Epirus

From a classical Greek point of view, the northwest of Greece was inhabited by a bunch of barbarian tribes, in which the fifth-century sources are nor really interested. They contradict each other about which nations could be classified as western Greeks, Epirotes, or Illyrians. It does not really help us that the tribes did not leave behind written texts. Several sanctuaries, like Dodona, appear to have been hellenized quite early, but the people of the northwest retained some archaic traits. Several tribes were led by kings, something that was very unusual in the Greek world. On the other hand, the nearby Macedonians shared some of these characteristics.

Like Macedonia, Epirus became a unified monarchy in the course of the fourth century. The tribe of the Molossians (in the interior) joined forces with the Thesprotians and the Chaones, and a more powerful state started to develop, with a king (Neoptolemus I), magistrates, coinage, a court, an assembly of tribal delegates, and a close alliance with king Philip of Macedonia. Supported by this powerful ruler, the unified Epirotes attacked and captured the Greek cities in the west. From now on, they had access to the sea. Urbanization started. The Molossian dynasty was sufficiently hellenized to claim descent from the homeric hero Achilles.

King Alexander of Molossis, a contemporary of Alexander the Great, commanded an excellent army and was considered to be civilized enough to be invited to support the Greek colonies in southern Italy. He seriously weakened the native Italian tribes, but was murdered after a defeat. His ally, Rome, benefited: it overcame the Italian tribes and started to unify Italy. Sooner or later, the Greek cities in southern Italy would have to face this new power.

In 330, Alexander of Molossis was succeeded by his relative Aeacides, who incurred the wrath of the Macedonian leader Cassander. In c.317 he organized a coup among the Molossians and put Neoptolemus II on the throne. After several difficult adventures, Aeacides' relatives found refuge at the court of another local king, Glaucias the Taulantian. He protected the Molossian royals and adopted Aeacides' baby son Pyrrhus.

The young king

Pyrrhus was born in 319/318 as the son of Aeacides and a Greek lady from Thessaly named Phthia, the daughter of a hero in the War of Greek liberation against the Macedonians (the "Lamian war"). The young boy grew up at the Taulantian court and was twelve when Glaucias made him king (306). It was obvious that Pyrrhus was to be some sort of puppet, and there was opposition among the Molossians. So when Pyrrhus visited his adoptive father to attend a wedding, his subjects revolted, plundered his property, and invited Neoptolemus II again (302). It is likely that Cassander was behind this insurrection.

However, Pyrrhus was not without support. In 307, the Fourth Diadoch War had broken out. Among the Successors of Alexander the Great, there was a commander named Antigonus Monophthalmus who attempted to restore the unity of the empire. He was opposed by men like Cassander of Macedonia, Seleucus of Babylonia, and Ptolemy of Egypt, who were attempting to gain independence. Antigonus' son Demetrius had invaded Greece, and Glaucias had allied himself to the enemy of his own enemy, Cassander. The alliance had been cemented by a marriage: Glaucias had given Pyrrhus' sister Deidamia to Demetrius as his bride. In other words, Pyrrhus and Demetrius were brothers-in-law. And Demetrius could use the young man against Cassander.

For the time being, he needed Pyrrhus in what is now western Turkey, where the great decisive battle between on the one hand king Antigonus and Demetrius and on the other hand the members of the coalition was fought at Ipsus (301). Pyrrhus fought bravely, but ultimately, the five hundred war elephants of Seleucus won the battle. Antigonus was killed in action and his son had to flee. However, Demetrius still possessed a large navy and had garrisons in the cities of Greece, where Pyrrhus may briefly have served as one of the governors of his brother-in-law. But not for a long time. In the negotiations that started after the battle of Ipsus, Demetrius agreed to hand over to his opponent Ptolemy of Egypt his wife's brother as a hostage. In Antiquity, this was a very common diplomatic practice: hostages ensured that the opposing sides would keep their promises.

So, in 300 or 299 Pyrrhus, not yet twenty, arrived in Alexandria, the Greek-style capital of the ancient country of the Nile, and it appears that pharaoh Ptolemy really liked the valiant young man, who gave proof of his strength and courage during hunting parties and other exercises. Ptolemy's stepdaughter Antigone became Pyrrhus' bride. (She was the daughter of Berenice I, who had once been married to an otherwise unknown man named Philip and had later married Ptolemy.) Pyrrhus' biographer Plutarch of Chaeronea remarks that the Molossian leader "had a particular art of gaining over the great ones to his own interest",note and this appears to be true. On the other hand, the great ones knew how to use Pyrrhus. In 297, Ptolemy financed a new coup in Epirus -the fourth one during Pyrrhus' life- and sent the Molossian leader with an army of mercenaries back to Epirus.

Pyrrhus played his cards carefully. He announced that he would share power with Neoptolemus, who believed the promises of the man who was, after all, his relative. Pyrrhus became king of the Molossians and leader of the Epirote confederacy for the second time, and acted as Ptolemy's watchdog in Europe, guarding the Egyptian interests against Cassander of Macedonia.

From now on, Pyrrhus started to embark upon larger projects. In 295, he killed Neoptolemus during a banquet and was able to make his people believe that his colleague had been disloyal. Having secured his rear, he went for the big prize: the Macedonian kingship. In 298, Cassander had died, leaving the throne to his son Philip IV, who had died within two months (of natural causes). His two brothers had divided the kingdom: Antipater received the western and Alexander V the eastern half, the river Axios being the border. As was to be expected, they immediately started to quarrel. Alexander felt threatened, and invited Demetrius and Pyrrhus to come to his assistance.

Pyrrhus invaded Macedonia in 294 and restored the balance of power between the two brothers. As a quid pro quo, Pyrrhus was to receive a part of Molossis that had been conquered by Philip II of Macedonia, and the city of Ambracia (modern Arta). This was to become Pyrrhus' capital: a city with access to the sea that was neither Molossian, nor Thesprotian or Chaonian.

Pyrrhus may have had greater designs, but for the time being, he had to be content, because in the meantime, Demetrius had arrived. King Alexander went out to greet him and thank him (for nothing), and was killed by Demetrius during a banquet - a repeat of Pyrrhus' treatment of Neoptolemus. Almost immediately, the Macedonian army proclaimed Demetrius king (text). He went on to attack the second brother, Antipater, who fled and never returned. Demetrius was the new Macedonian king.

Meanwhile, Pyrrhus' wife Antigone had died, and the king of Epirus remarried to three other women. His first bride was a Greek lady named Lanassa, and her dowry consisted of the islands of Leucas and Corcyra (modern Corfu). She was the daughter of Agathocles, the king of Syracuse on Sicily. Pyrrhus also married to a daughter of king Audoleon of the Paeones (north of Macedonia), and to Bircenna, the daughter of the leader of the Illyrians, Bardyllis. Through these marriage ties, Epirus was now at peace with all its neighbors - including powerful Macedonia, where the new king Demetrius was married to Pyrrhus' sister.